ROCHEFORT (PART II)

ROCHEFORT: A DETAILED DISCUSSION OF PLANS

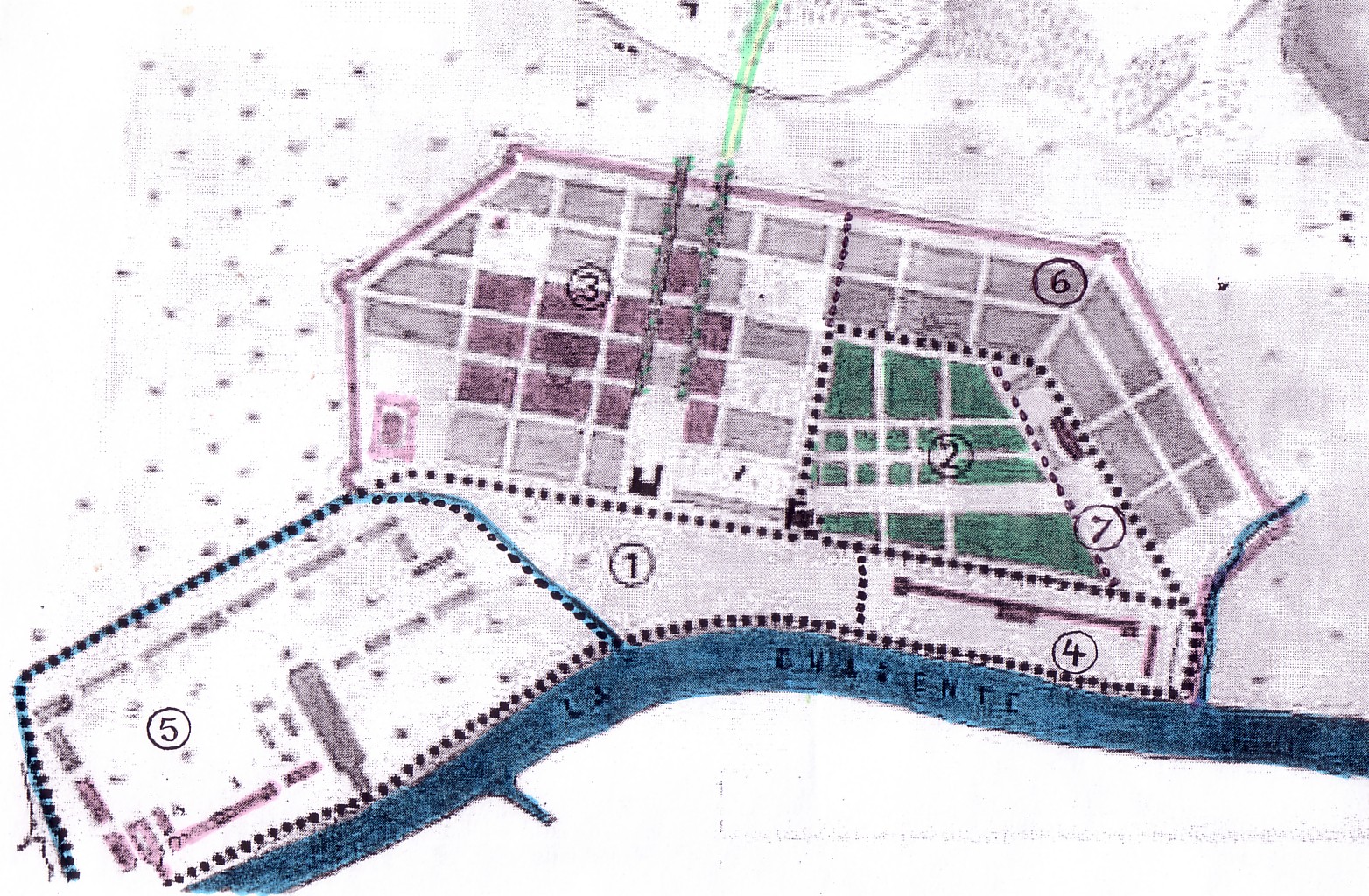

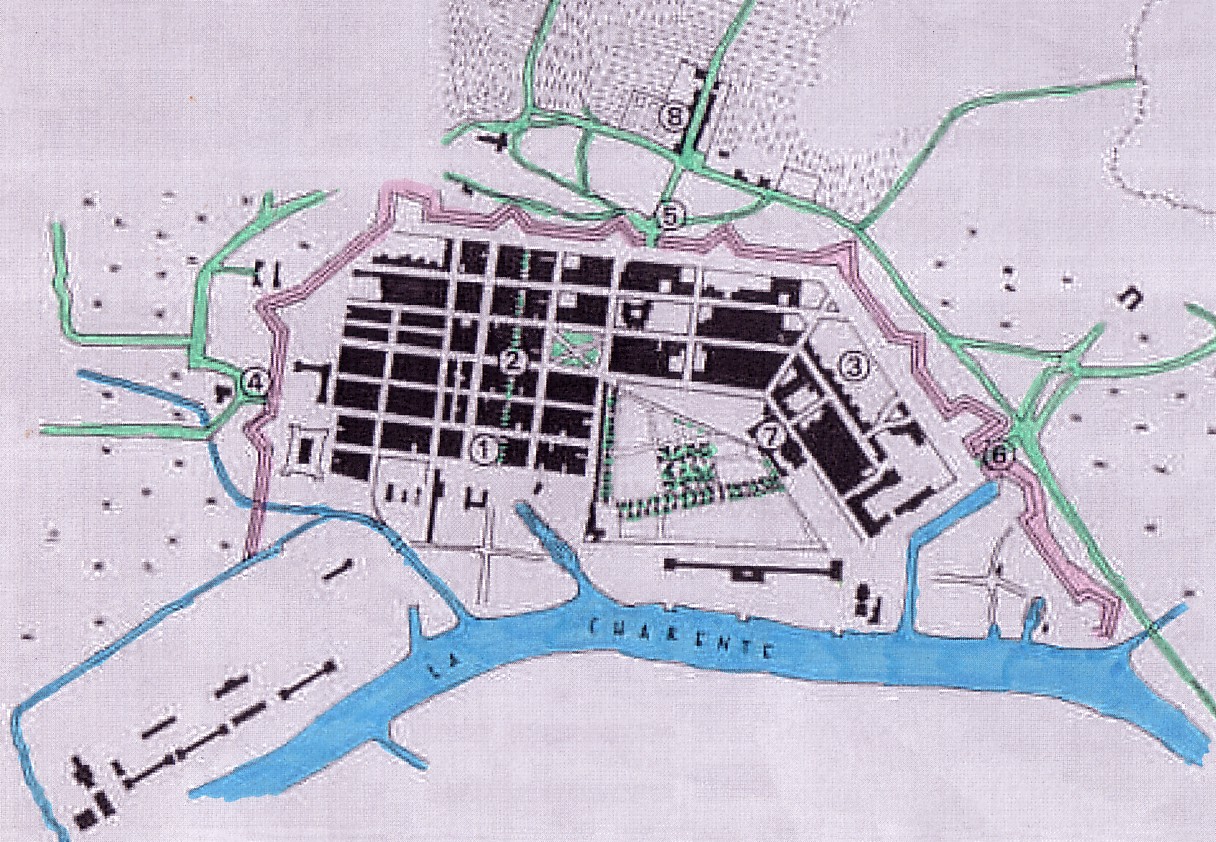

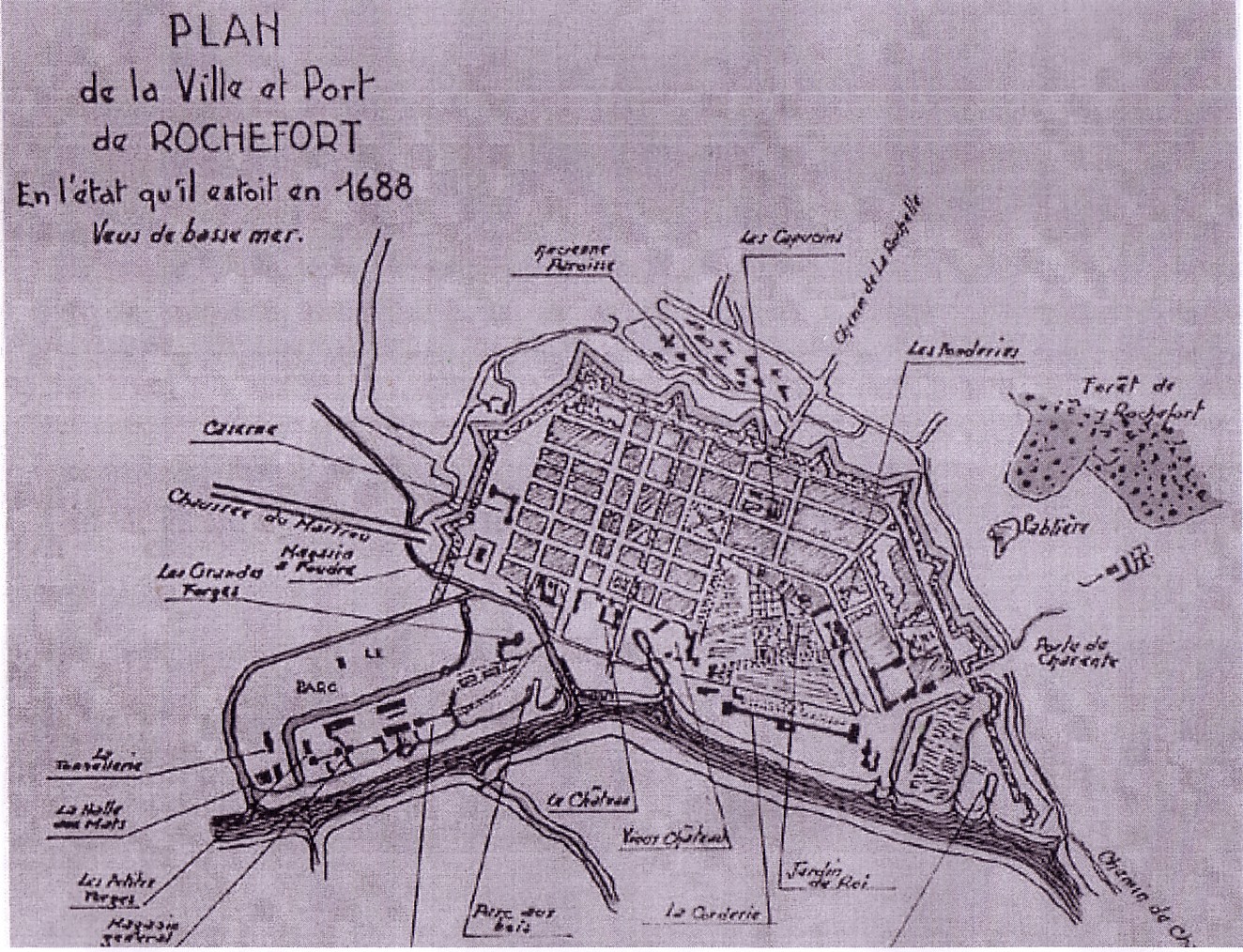

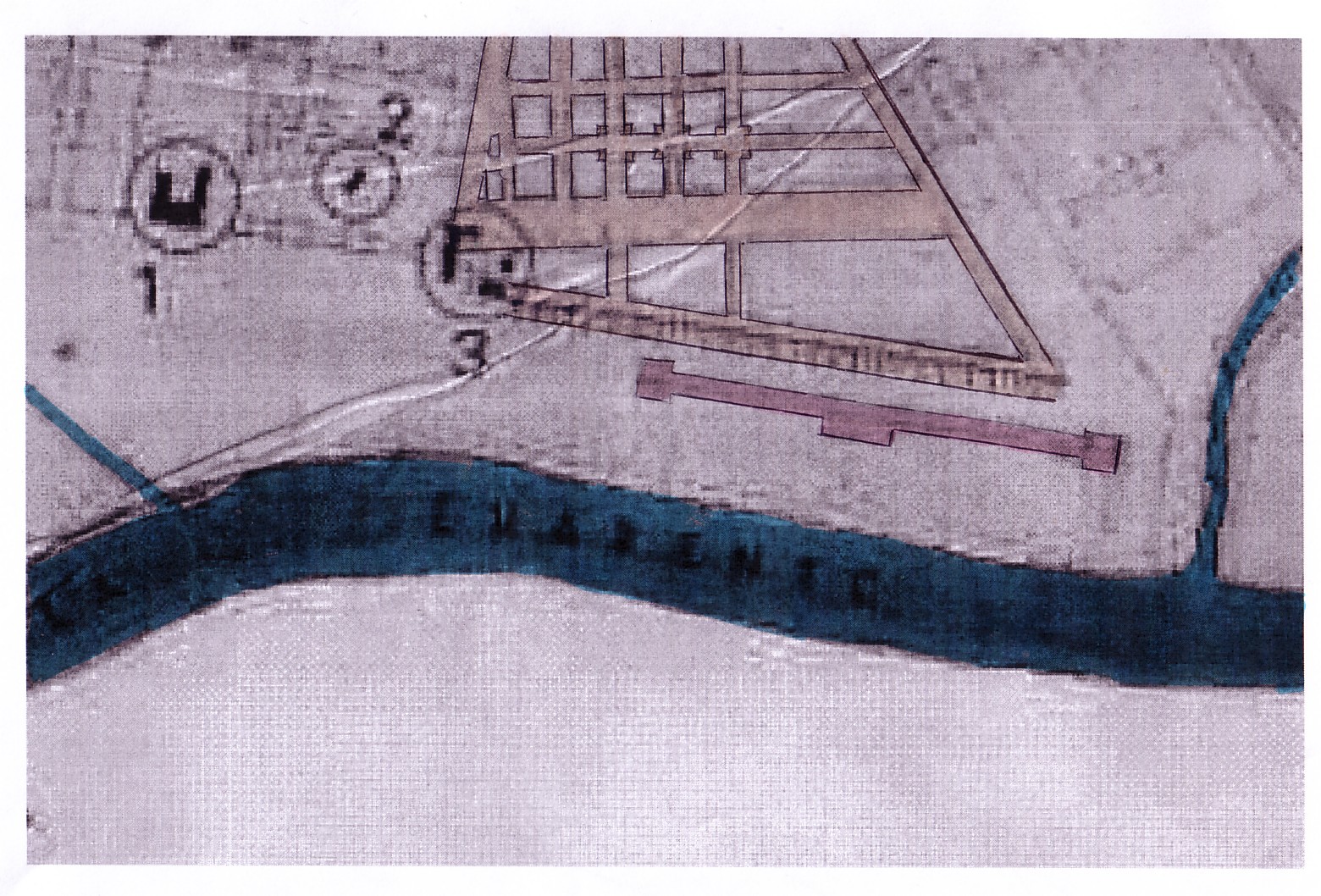

Rochefort from the very beginning

was a planned town on a site chosen next to the Charente though

not, as a town, situated directly by the riverside.

1666

1666

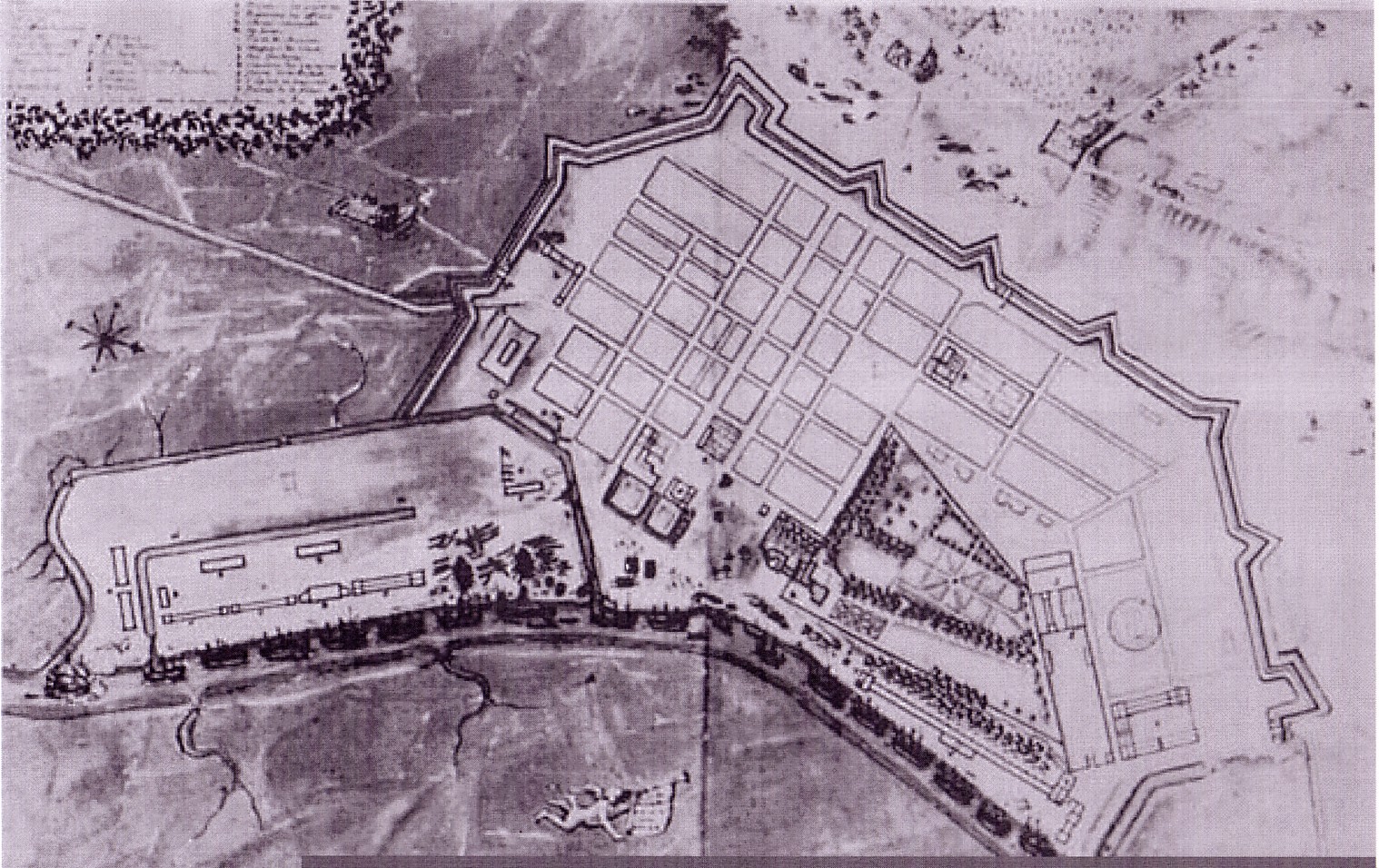

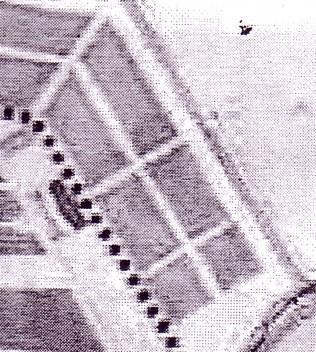

The planning proposal of 1666; construction of the Corderie

begins in the same year

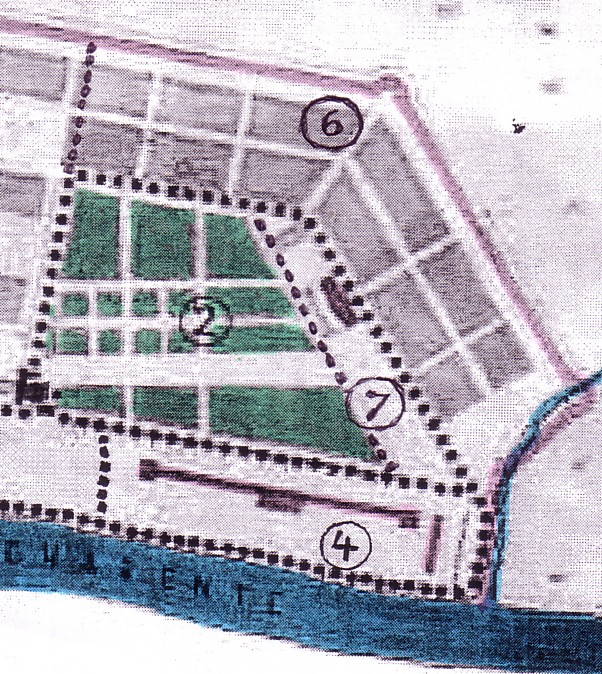

The well-laid-out town (3; 6; 7)

was separated from the river by 'industrial' terrains: the Corderie in

the North (4), the 'arsenal' proper to the South (5), and the 'wasteland'

of the former local 'port' (the old 'quai' or mere local embarkement and

disembarkent site) in-between (1).

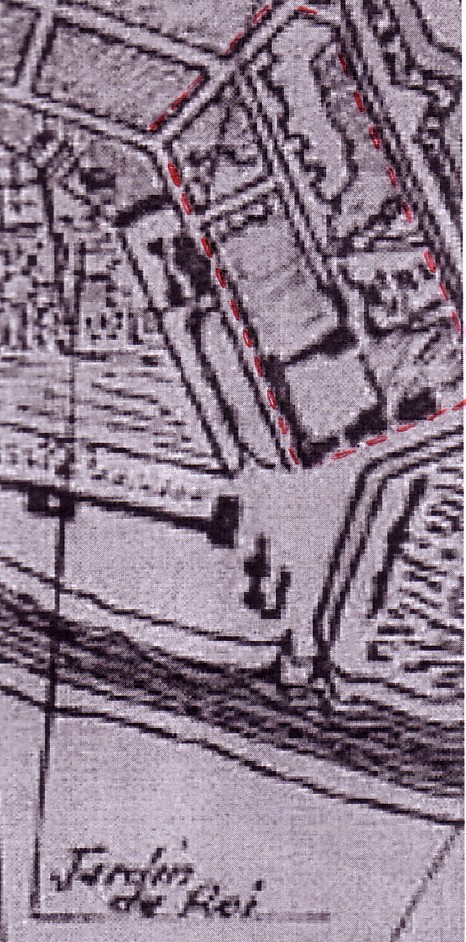

Rochefort in 1672 "when construction of the arsenal buildings

was completed"

But there is a different way to look at the differentiation of terrains, not in terms of an 'industrial' and a 'dwelling' function but in terms of 'royal' (respectively State) or 'bourgeois' (respectively private) ownership.

For it was only the well-laid-out town (3; 6) which was parcelled and then given in a piecemeal fashion, during the early years of this city, to newly arriving private owners.

The large chunks of 'industrial'

lands remained State property (4; 5; 7).

It is here that considerations

of royal prestige and representation as well as functional

(production and maintainance) needs of the Navy played a role that

can hardly be overlooked. In fact, this combination of representational

and productive function is especially potent in the Northern part

of Rochefort where the terrain of the Corderie and the terrains

of the future jardin royal meet. Both, in my view, form indeed

a unity: the space that I would like to call the real 'ville royale'(4;

2), as against the 'ville bourgeoise' that coexisted with it (3; 6).(1)

We

will come back to this context of Corderie and jardin royal a

little later.

* *

*

Let us look first, however, at the

plans of Rochefort that other researchers, notable Maxime Lonlas,

have presented to us.

1666

1666

Again: the original plan (with additions [the main axis,

plus pre-existing items 1, 2, 3] entered by M. Lonlas)

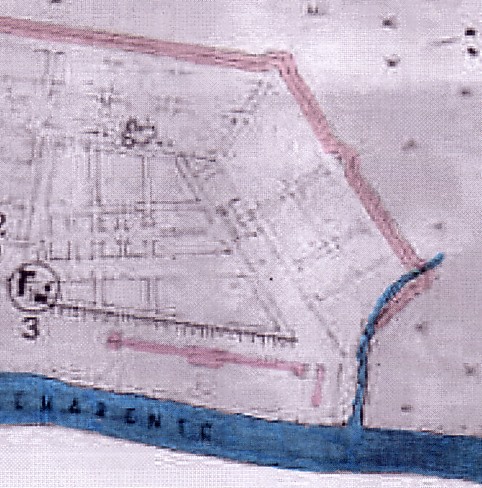

It is the 1666 plan that already shows the basic concept of a town backing up the Corderie in the North and the navy yard to the South of it. The two 'wharfs' envisaged (as part of the 'arsenal proper) are already indicated. The corderie is entered as if functionally existing already, and so is the powder magazine near the Southern ramparts.

Leading west, from the new château (added to this plan by Maxime Lonlas), we find two tree-studded alleys (also added by M. Lonlas). They will form the backbone of the 'ville bourgeoise' springing up around it in this Southern part of the grid.

There are only very few other buildings

indicated on this plan, most notably the 'Foundry' (Les Fonderies)

to the West of the Corderie and North of the adjacent future 'royal garden.'

The buildings of the arsenal proper,

the powder magazine, the Corderie, and the Foundry were all important functional

elements of the navy arsenal project; they figure on this earliest plan

of Rochelle drawn in the year of Rochelle's foundation, and they

were all realized subsequently.

17th C

17th C

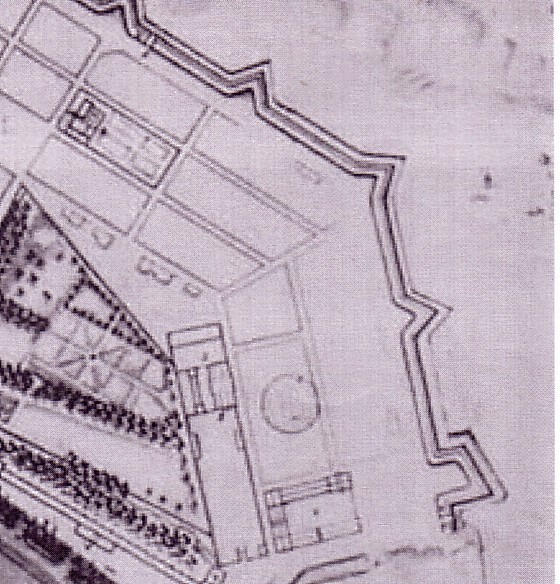

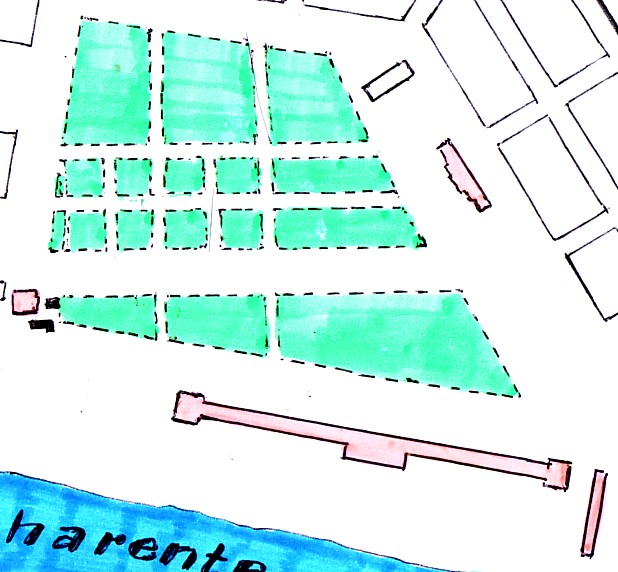

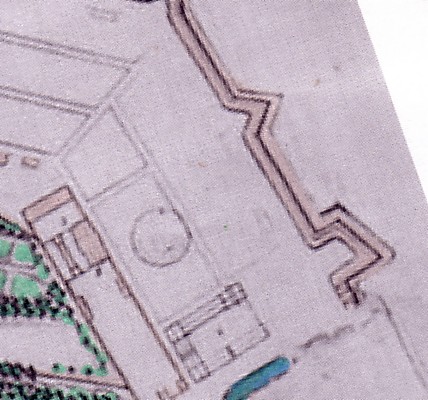

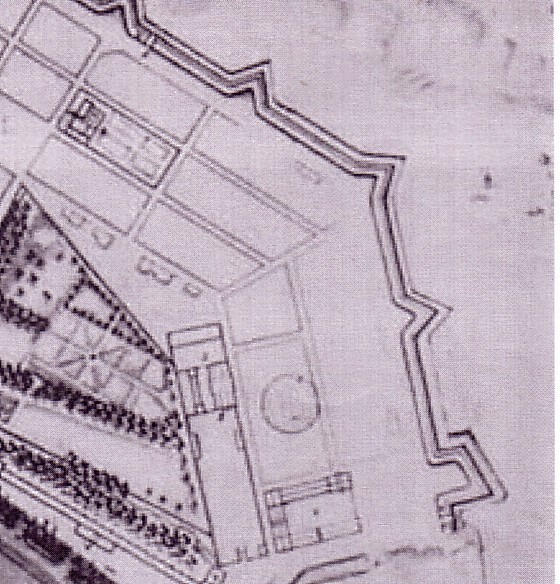

The undated 17th C plan

This undated plan from the 17th

century (shown as an excerpt, without most of the 'arsenal proper') gives

us the most concrete impression obtainable of the urban development that

took place in the early years. The monastery of the Capucins with

garden lands to the North of it is shown on a block in what is the Southern

fringe of the Northern part of the 'ville bourgeoise' (as we have defined

it above).

The other blocks of the Northern

part of this well-laid-out town are still, for the most part, empty. This

is confirmed by Maxime Lonlas's reconstruction of the building process

up to 1672, superimposed on a plan of that year.

However, just West of the royal

garden we see four houses, outside the grid pattern, that is to say, between

grid and the wall surrounding the 'jardin royal.'

They are, so to speak, marginalized

houses. Workers houses, in the shadow of the garden wall, and close enough

to the foundry and Corderie? We can only suggest this as a hypothesis.(2)

1666

1666

In 1666, a 'street pattern' is recognizable on the terrain that

was to form the 'jardin royal'

but it does not connect properly with the grid West of it. To

the north, one of its "streets" is

'visually' continued into the 'ville bourgeoise' but the building

marked in red interrupts

this connection

The royal garden is very visible

indeed. It is lacking the clear 'street pattern,' however, that was envisaged

in the 1666 planning proposal and that recurs on the plan of 1672. The

layout of the garden corresponds rather with the one visible on the plan

of 1677.

This would suggest that the plan

was produced later than 1672.

It is only the more strange that

the built-up or partly built-up blocks identified by Lonlas on the

plan of 1672 do not appear on this (apparently later) plan as studded with

buildings.

Is the undated 17th century plan

that is being discussed here showing only public and church buildings?

Let us now come to the 1672 plan.

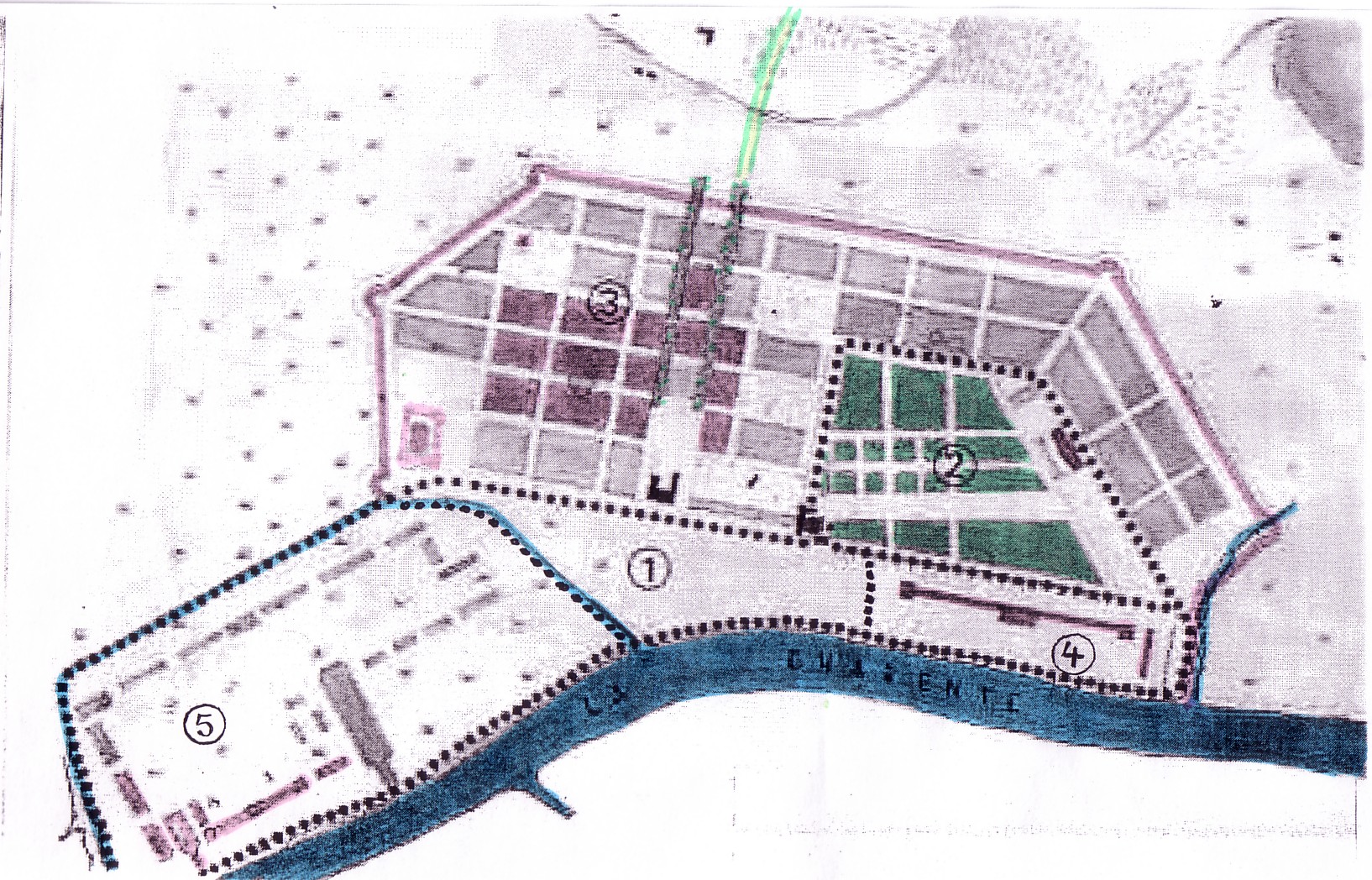

1672 is the year when the Corderie and the first sequence of buildings

in the 'arsenal proper' had been completed. It is this 1672 plan on which

M. Lonlas superimposed his information as to "parties [in fact, blocks]

bâties ou en cours de construction" (blocks built up or under construction).

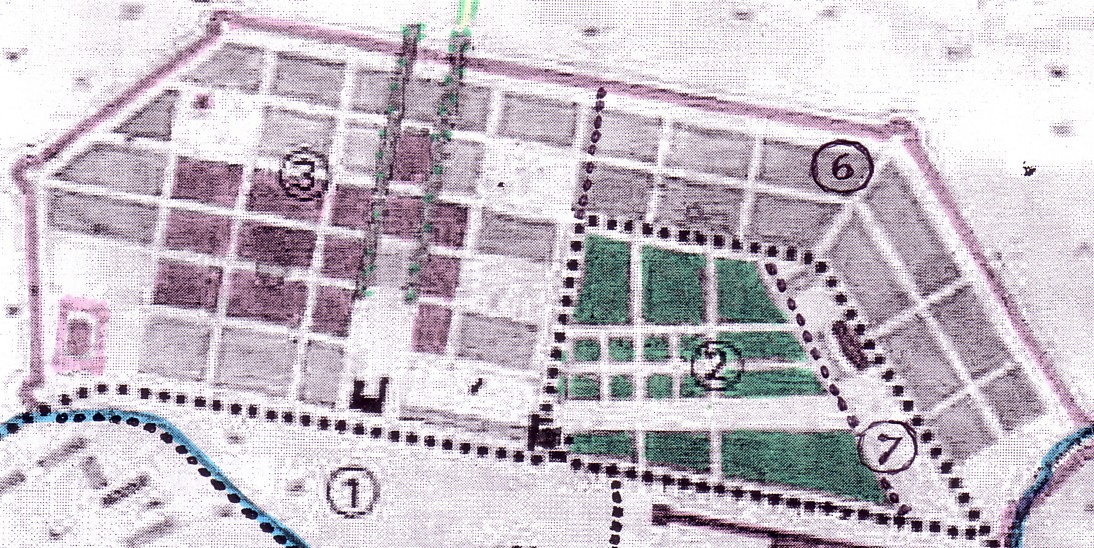

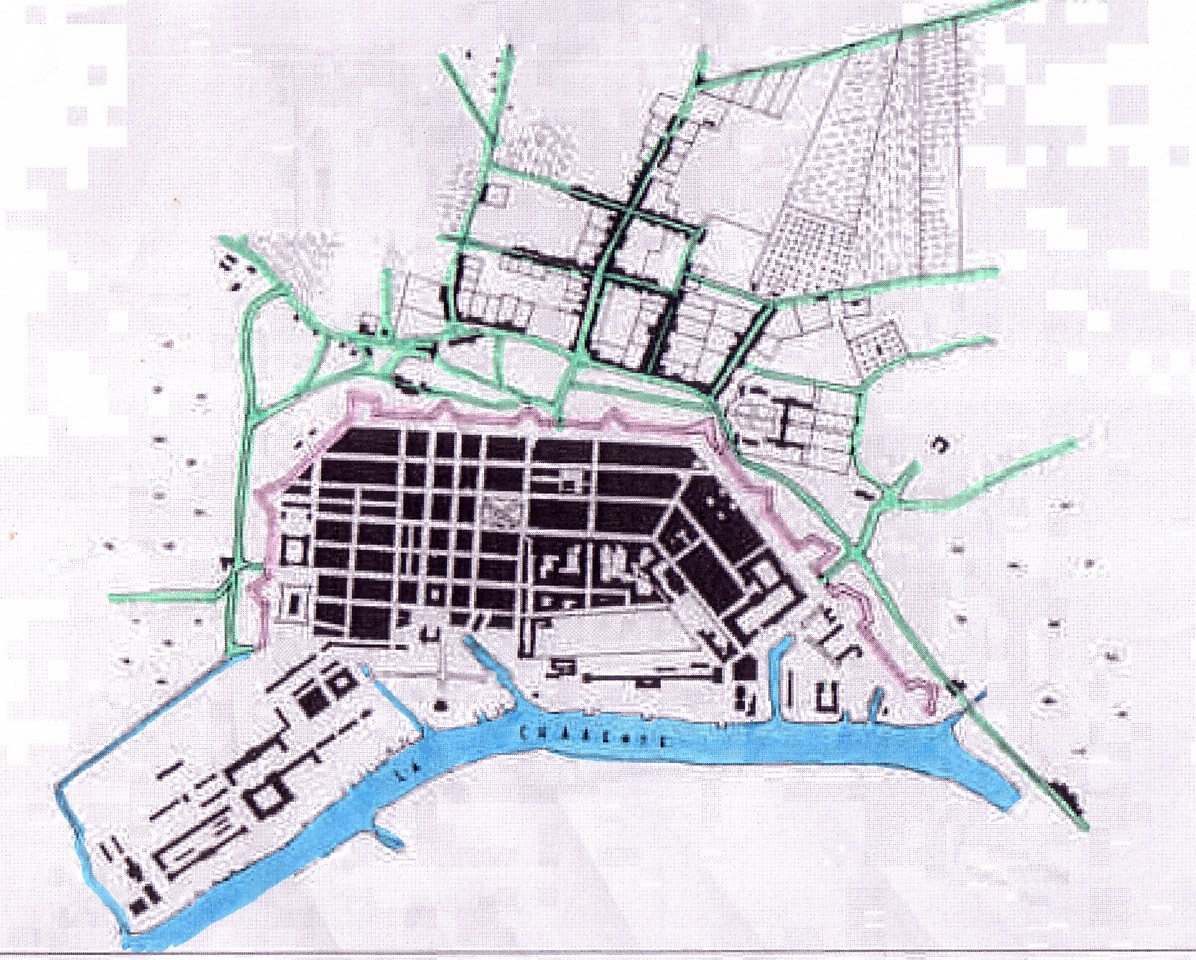

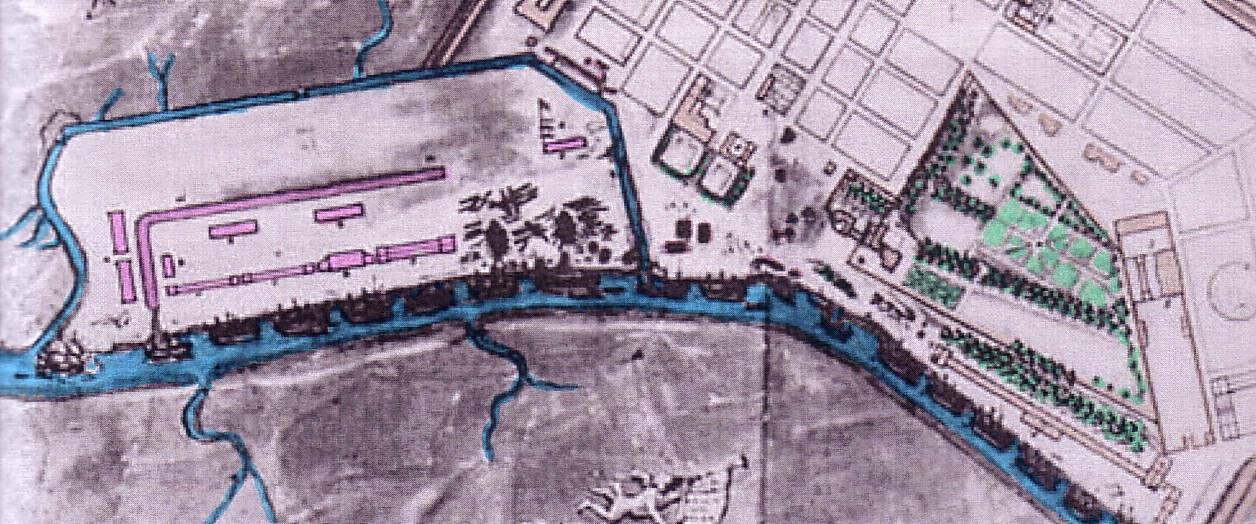

The 1672 plan

The 1672 plan

The plan as shown here is the historical plan of 1672, with subsequent additions of information by Lonlas (and additional coloration of a black and white scan).

As no built-up blocks (within the

grid) are indicated in the Northern part of town, we shall first look at

the Southern section.

West

--> N

--> N

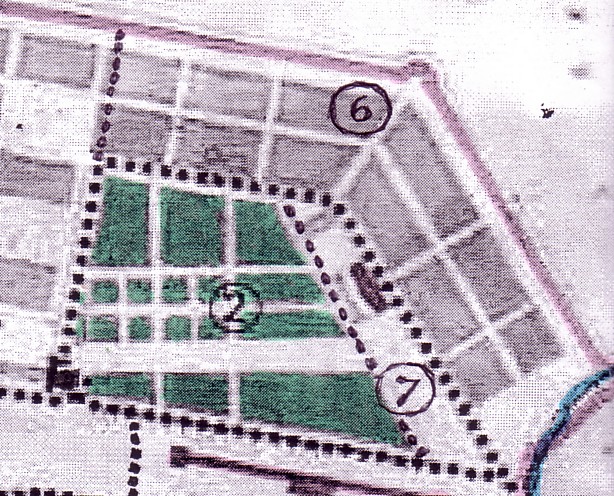

Southern part of the 'ville bourgeoise' on the 1672 plan

(The blocks colored in dark violet are considered

as 'built-up areas or under construction,' by Lonlas)

The two tree-studded alleys leading

westward from the new château form the main axis, as we have already

mentioned before.

In front of the château,

there is a wide, elongated, rectangular square, comparable to the 'Paradeplatz'

of Mannheim (another absolutist 'new town', in Baden; Southwest Germany).

In all likelihood, the 'sought-after'

lots were in the neighborhood of the château and along the main axis.

It is hardly imaginable that lots were handed out here to construction

workers and later on to arsenal workers in order to have them erect their

makeshift huts or 'cabanes.' Rather, representative buildings can

be expected, perhaps even executed in stone.(3)

Rochefort was not only a place of

work, of production and maintenance of and for the French Atlantic Fleet.

The

works entailed a huge financial input from the State coffers. The

value involved in acquiring finished goods (guns, muskets, etc) for

the navy, of acquiring raw materials such as iron and charcoal for

the forges, hemp for the ropemakers in the Corderie, sail cloth and tree

trunks for the shipbuilders of the arsenal, special wood for the coopers

of the 'tonnelerie', and so on and so forth, certainly required supervision.

As did of course the planning and

construction effort of the town and the arsenal itself (which was at best

half completed after 7 years in 1672).

In other words, there were administrators

to be housed: the nephew of Colbert and his underlings, but also, we may

assume, a local representative of the Paris-based intendant of the navy

[secretary of the navy; 'Marine-Minister'). Even though quite a few capable

administrators may have been of bourgeois origin, these commoners were

coopted by the ideologically 'aristocratic' ancien régime and formed

the noblesse de robe. Others were 'genuine' aristocrats. As representatives

of royal authority, they must be seen as 'requiring' privileged accomodation

in privileged sites.

Thus we may assume that many officials of the regime were housed in more or less representative dwellings; the top layers (a few only) even in so-called hôtels, in other words, almost 'palace-like' townhouses (Stadtpaläste) or 'mansions.' All or most of these dwellings can be expected along the two main East-West alleys of the new town, with the best sites (as mentioned) close to the château.

But let us not forget the wealthy

bourgeois stratum attracted by and developing in such a port city. We have

already spoken of the arms dealers, the wine merchants, the suppliers of

sail cloth, of hemp, of wood (bois), and so on.(4)

They, too, depending on their income

and prestige, were prone to look for respectable sites where to build their

new house in the new town.

As the number of wealthy and prestigious people, no matter how considerable it was, was still small in comparison with the work force employed in Rochefort, we can imagine that the construction process of the respectable parts of the new town was a slow one.(5)

But these thousands of workers whose

presence in the works of Rochefort cannot be doubted were certainly direly

in need of accommodation as well. Were would they find it?

We can only speculate at this stage.

Our best guess is that at least some of these members of the 'subaltern

classes' found accommodation in certain less prominent blocks of the grid

patterned town, perhaps close to the powder magazine, or elsewhere in unfavorable

locations close to the ramparts.

Now the fact is that the plan of 1672 shows the block occupied partially be the powder magazine is otherwise empty. The block immediately to the West of it is also empty. In a way this is not astonishing - for who would like to live next to a gun powder storage facility? But the 3 blocks further West, next to the Southern ramparts, are also left empty, and so are the 6 blocks of the Southern part of the well-laid-out town which are situated next to the Western ramparts.

Lets us look now to the blocks close

to the arsenal proper and next to that 'waste-land' formerly occupied by

the 'old quai.' They too are empty!

All the sites imaginable as less

favored sites, likely to be occupied by the subaltern classes of a town,

are still uninhabited in 1672!

This is strange, isn't it?

Where did the thousands of workers

live? Where did those men and women who came to find work here and

who were given a building lot and 'bois' (wood) to build a house, proceeed

with the construction of their poor, makeshift dwellings?

We will come back to that question later.

But first, let us return to the

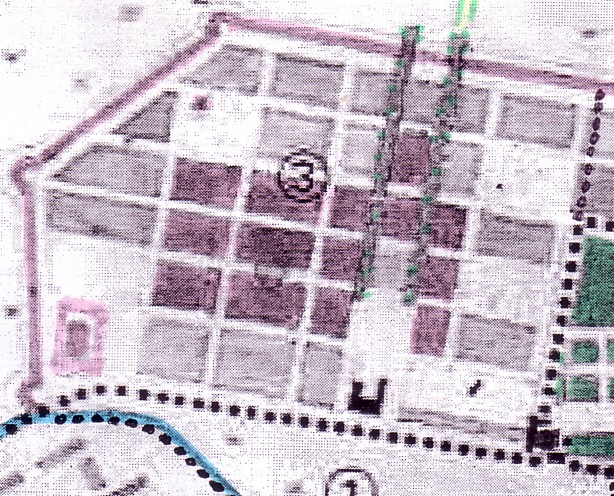

1672 plan, that is to say, its Northern section.

It is possible (but the quality

of the plan reproduced is not very good) that on the 2nd of three blocks

bordering on the Western edge of the 'royal garden,' two (or more?) houses

can be identified.

West

--> N

--> N

Northern part of the 'ville bourgeoise' (1672 plan)

17th C

17th C

This 17th century plan shows a different grid pattern, and the houses shown on that plan West of the royal garden are by no means identical with the houses that may be shown in roughly the same area (but a little further west) on the 1672 plan.

Is it possible that even in this

early phase of Rochefort's urban development (when only a small part of

the town conceived had been realized), houses were broken down and replaced

by others?

Certainly streets planned were

altered; the size and shape of the rectangular blocks and thus of the grid

underwent adjustments.

The blocks to the North of the royal

garden are traversed by a street departing from a solid building quite

close to the northern edge of the jardin royal - the fonderie?

Along this street the historical

plan of 1672 may also be showing houses - if we do not mistake 'impurities'

of the reproduction for an indication of such built structures.

At any rate, according to Lonlas,

neither of the blocks discussed here in the Northern part of the well-laid-out

town should be considered as at least partially covered by buildings. Is

he 100% right in claiming there were no buildings in this part of

the grid-based 'ville bourgeoise'? Or is he just tendentially right in

indicating (which is very important) that the construction process of the

new town was centered in its Southern part ((3), on our plan further above),

whereas the Northern part ((6), in our above plan) was essentially bypassed

in the first decade(s)?

1672

1672

Built-up or partly built up blocks in 1672 according to Lonlas (only in the Southern part of town)

1677

1677

Built-up or partly built-up blocks in 1677

(according to Lonlas)

The jump from 1672 to 1677 comprises

a mere 5 (or 6, if we include both 1672 and 1677) years.

If we remember the comparatively

"small" number of blocks in the Southern part of town that were at least

partially built up ("bâties ou en cours de construction", according

to Lonlas), the extension of the built-up area of Rochefort in 1677 is

truly amazing.(6)

In the Northern part of the town, the block encompassing the monastery of the Capucins is still for the most part covered by their garden land. The grid pattern is identical to that of the undated 17th century plan shown above while the grid pattern as shown on the 1672 plan has been abandoned.

The 'triangle' shown on the undated 17th century plan as covered with 4 buildings close to the Western wall of the 'jardin royal' is shown in 1677 as completely empty.(7) Has the undated plan originated later than 1677, or have these buildings been broken down?

The 'fonderies' (foundries), indicated by (7), thanks to Lonlas, on the 1677 plan, are very prominent indeed. On the block marked with a (3) in 1677, we see a long and rather narrow row of houses - workers' houses? Perhaps.

The almost U-shaped form of houses lined up along three sides of the block next to the Northern ships' basin must be a public building. Three of the four sides of the block are shown as covered with buildings (Blockrandbebauung) on the undated 17th century plan.

The grid changes 'continually' in

this part of the 'ville bourgeoise' to the North of the royal garden.

It is made up of 6 blocks on the

plan of 1672, of 4 blocks and a fairly large square in front of the Northern

city gate, on the undated 17th century plan, and of 4 blocks very

different in size and shape (one L-shaped) on the 1677 plan.

In 1672, the basin where ships

would be loaded and unloaded did not yet exist but it is shown on the other

two plans.(8)

As for the lay-out of the royal

garden, this is not stable, either.

The garden itself is (out

of carelessness? or because walls did not yet exist) shown without a surrounding

wall on the 1666 and 1672 plans, but it is shown to be sheltered

by a wall on the 1677 plan and the undated 17th century plan.

Of course, whether a wall existed

or not made quite a difference.

Without the wall, the garden posed

no obstacle if Corderie workers really relied on housing hurriedly constructed

to the west of the garden. As soon as the walls existed, they immediately

cut off the blocks to the West of the royal garden from the Corderie. The

'foundries' were sheltered by a wall, too. Any living quarter to

the West of the garden and the foundries would therefore require a considerable

detour for Corderie workers possibly depending on such accommodation.

In fact, both the six (later on,

four) blocks of the Northern part of the well-laid-out town that

were

situated to the West of the garden

and the entire Southern part of the well-laid-out town were not comfortably

attainable from the Corderie site.

If the Corderie employed a massive

number of workers, the town seemed to be not for them - at least in spatial

terms, from the point of view of how it was planned.

West

1677

1677

Rochefort and the emerging Western faubourg

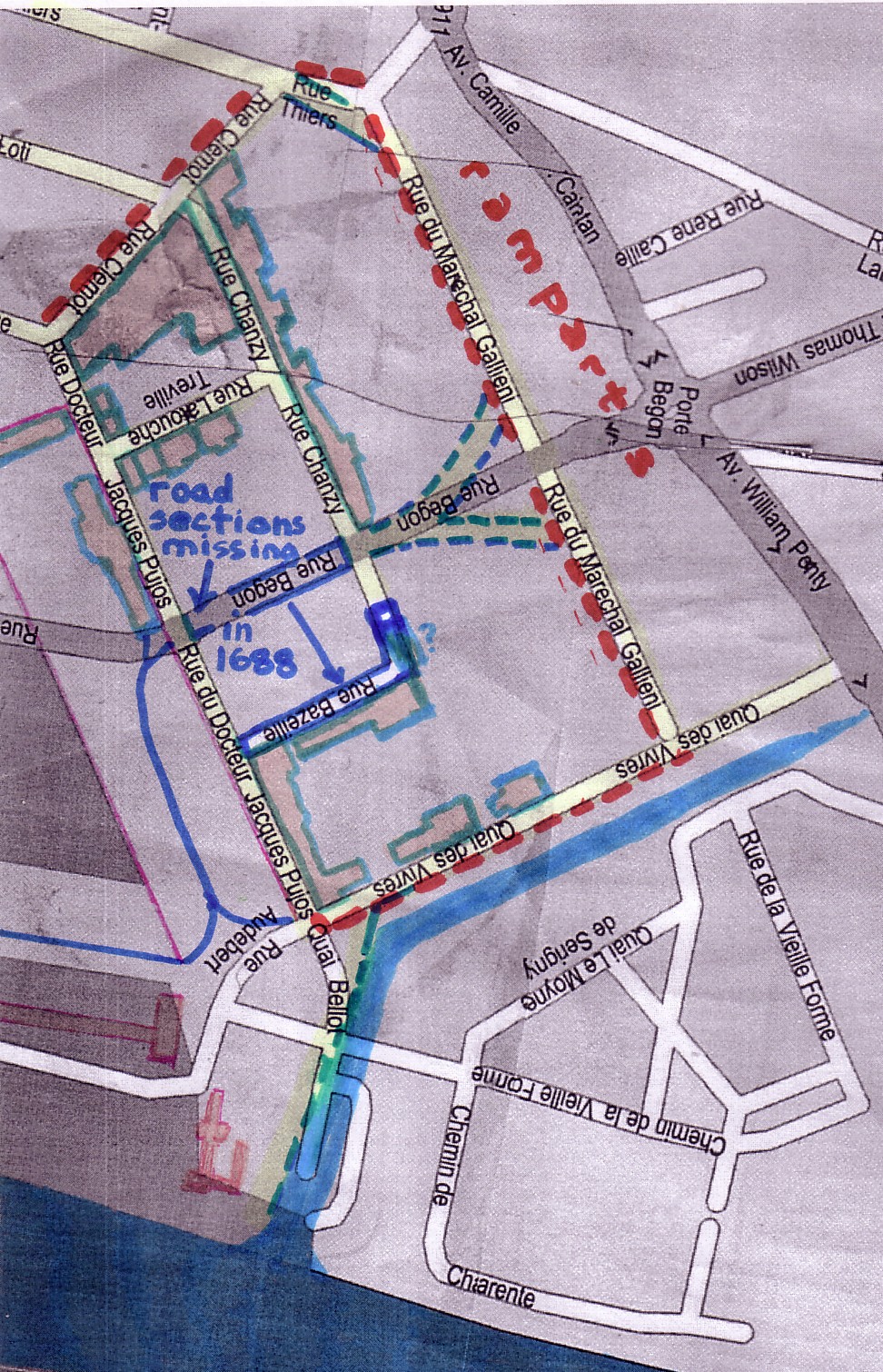

Let's now briefly turn from the 1677 plan (shown here in its entirety) to a plan drawn up only 11 or 12 years later, in 1688.

The 1688 plan shown below has the disadvantage of less optical clarity, in comparison with the 1677 plan that has been redrawn with all the carefulness of an architect by Lonlas. The later plan has the advantage, however, of identifying individual buildings (information we have relied upon, further above, and will continue to rely upon). In order to make full use of this 1688 plan, we shall have to look at individual sections (enlarged plan excerpts).

1688

1688

Indication of public buildings, gates, Capucin monastery,

etc on 1688 plan

For the sake of a desirable completeness

of information (to the extent that we can offer it), we make also available

the two following plans, of 1724 and 1845.

1724

1724

Rochefort and the Western faubourg 1724

1845

1845

Rochefort and the Western faubourg 1845

These latter plans are especially

interesting if we regard the development of the western faubourg, something

Lonlas that noted as well. We will come back to it later on.

* * *

Our attempt to offer more detailed views (close-ups, so to speak), lets us turn once more to the Corderie, the 'core' from which Rochefort was to develop.

The Corderie

1666

1666

The plan showing the projected Corderie.

The Corderie was the first new building of the 'Rochefort' project

The site of the Corderie today

The site of the Corderie today

From an empirical point of

view, despite all older (pre-1666) remnants, the Corderie was the true

nucleus, the starting point of the 'new town' that was to be Rochefort.

It was an impressive building that required vast funds

to be produced, and an enormous work force. It was the supreme mark left

in this area by the government of the roi du Soleil.

It is for the architects to describe and comment on its

characteristics.

Let it suffice here to point out that, in terms of its length, this almost palace-like building totalled 300 meters: enormous indeed for any 'manufactory.'

The reconstructed Corderie today

Its design reminds us of the fact that in the next, the

18th century, quite a few manufactories run by the State or as private

ventures by aristocrats (like Liancourt!) were set up in châteaus

re-dedicated to such a 'vulgar' manufacturing purpose. Wieser-Benedetti

and Grenier are mistaken if they think that the term "château d'industrie"

was initially merely a metaphoric one, awarded to mid- and late 19th century

factories (in the Lille region and elsewhere) because of the 'Gothic' design

of certain cotton mills with their multi-storied structures and prominent

towers added on to them for the sake of a mis-understood 'beauty.'

The Corderie was the starting point of urban development in Rochefort, we said. Indeed, in the initial phase of Rochefort's production, the Corderie must have been the only (new) structure visible in this desolate, devastated place by the Charente. Or almost so. For the barracks or 'cabanes' of the construction workers were its counterpoint. Although less visible to historical researchers (and certainly on historical plans), contemporaries coming to the construction site cannot have failed to notice them. But those who were to write about the endeavours of the government would not dwell on such poor habitations. And the villagers in hamlets nearby would neither know how to write about these shabby dwellings, nor would they see them as especially noteworthy. Their 'cabanes' were probably only a little more solid, a little more comfortable.

* * *

The Corderie: Where did its workers live?

Where did the ropery workers live?

This is a question we must ask.

In view of the fact that the Corderie

was the first and foremost manufactory building of Rochefort in the 17th

century, an enormous building 300 meters in length, this question how and

where its obviously considerable work-force was housed is not to be taken

lightly.

The reconstructed Corderie (photo from the Merimee data base, Ministry of Culture, France)

As we shall see, the Corderie was rather effectively separated, in urbanistic terms, from the bourgeois town that was slowly being produced. This separation is effected visually, as well. Right behind it, there was a small 'bois' (as they say in French): less than a forest, and more than a grove, wider than the Corderie itself and about the same length (300 meters). On other plans, it is supplanted by a long row of trees, planted along a straight alley.

Behind this 'bois' respectively

the row of trees, more prominent visually than the alley itself,

there was the walled-in compound encompassing what was seemingly a private,

royal or aristocratic park which incorporated, at its Southern fringe,

the old château, razed some forty years ago.

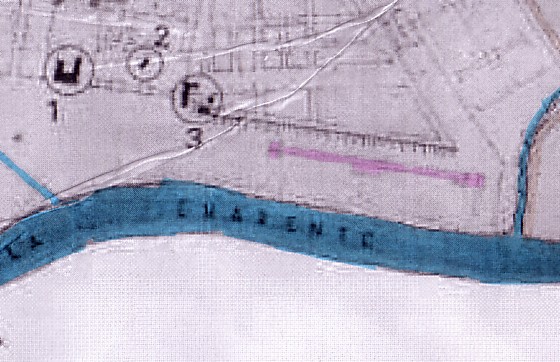

=>N

=>N

The Corderie and its immediate spatial context

This separation, in terms of spatial

relations to the "town," foreshadows a hypothetical question if not conclusion:

Where

the Corderie workers housed in the Corderie itself?

Such a solution was clearly an

option not infrequently chosen by manufacturers in the 17th and 18th century:

Employees could be put up in the manufactory building itself, either in

side wings (that actually exist in the Rochefort case) or else "right

below the roof," in the attic (the rather markedly visible 'mansardes')

- if that space was not reservcd for storage of raw material.

The wings as well as the 'mansardes' of

the Corderie cannot be overlooked.

In addition, a rather large house in the

background, North of the Corderie, is visible on this photo

Still, there are other alternatives to be considered.

If accommodation of workers outside the Corderie area may have implied a long journey to work to the nearby hamlets, or a somewhat shorter journey to one of the few completed houses existing rather early on (as we shall see) in the Northern part of the well laid-out 'bourgeois town,' it becomes apparent that these solutions were hardly the best way to house workers. To what extent either of these alternatives played a role, we do not know.

However, we do know that in addition to the options pointed out already, further strategies of housing the work force of the Corderie may have played a role.

There was, in fact, another possibility, and that concerned various minor buildings, belonging (unmistakably or only 'perhaps') to the Corderie.

In the photo above, we see in the

background, at a certain distance, a rather large house, erected

in a perpendicular direction, with regard to the main building of the Corderie.

Actually, plans show that there

were at time two and even three buildings to the North of the Corderie,

situated somewhat closer to the river than the Corderie itself.

The building to the North of the Corderie that is visible on the

photo above

is shown here on a plan that we date as post-1672 and pre-1677

The plan of 1677 shows two more or less parallel buildings just North of the Corderie

Another possibility is that some

workers were housed right behind the Corderie, in the small house behind

its Southern wing..

The Southern wing and what appears like

an entrance to an 'inner court,'

later on produced in the back of the Corderie.

Was it partly framed by low buildings?

This photo shows that there was

at some time an inner court just behind the Corderie, framed (at

least partially) by one-storeyed buildings. However, these buildings do

not exist on the plan shown above.

The possibility that they functioned

as accommodation for Corderie workers cannot be excluded.

* * *

The Corderie royale (first and most expensive building),

the arsenal, and the town form

a functionally related "unity" made up of

three constitutive, separate urban 'spaces' or parts

We have elsewhere identified 7 distinct urban "spaces"

and this, we believe, with good reason. But in a sense, Lonlas also is

right if he identifies three urban "spaces": for him they are (a) the arsenal

(including the Corderie), (b) the royal garden, and (c) "the town."

- We would rather suggest: (a) the Corderie, (b) the 'arsenal proper',

and (c) "the town."

undated plan, 17th C

undated plan, 17th C

The triangular relationship of (a) Arsenal, (b) Corderie and (c) "the town"

The same, as a 'close-up'

It was the Corderie, and not the well-laid-out town, which was first realized. But in fact, we must not forget that the Corderie royale (though ostentatively separated from the town), the arsenal (separate, too), and the town (la ville) form a functionally related unity made up of three constitutive, yet separate urban 'spaces' or parts.

While the Corderie and the arsenal, although spatially

separated, fulfilled a productive and maintenance function with respect

to the royal navy, the town (which is adjacent two both) fulfilled three

functions: it provided lodging to a population, it served as a commercial

center, and it fulfilled an administrative function with regard to the

naval base and the fleet.

* *

*

We shall now continue with

our task of looking "more closely" on diverse parts of the town.

In

line with a major research interest of this study, we shall keep in mind

the question where the employees of the major works of Rochefort

may have found accommodation in the period between 1666 and 1850. Our main

focus in this respect will be on the earlier periods, that is to say, the

17th and 18th century.

Let us begin here with the NORTHERN

SECTION of Rochefort.

Of course, the Corderie is once

more our point of departure.

As noted already, the Corderie must have been a major employer - both during the phase of its construction (when 3,000 workers were toiling to construct it) and after its completion when it functioned as a ropery.

But the Corderie, it was noted, was also a fine building, marvellously executed in order to reflect the power and the glory of the roi du Soleil.

Early plans indicate no wall separating a royal garden from the Corderie, Rather, the greens stretched out vastly in the back of it, forming a single unit with the magnificent Corderie itself. In truth, the Corderie was the center piece not of the 'arsenal' (its more modest ateliers being situated further South) but of the 'ville royale', the prestigious and representative 'core' of Rochefort which also preceded the 'ville bourgeoise' timewise.

Later plans, from at least

1677 onward, show, however, the Corderie as separated from the 'jardin

royale'. Its productive function was accentuated. The leisure function

of the garden now was a separate matter, and (thanks to the surrounding

wall) quite literally so.

1672

1672

Despite the later accentuation of

the productive function (the separation of the Corderie from the 'jardin'),

the

representative execution of the Corderie ((4) in the 1672 plan)) and the

creation of the royal garden(2) must have had implications for the Northern

part of the well-laid-out 'bourgeois' town in the back of it, from the

very outset (6).

The Northern section of the town (conceived, primarily, as a 'bourgeois' town, in terms of a correct grid-pattern formed by 6 blocks on the plan of 1672) was not only effectively cut-off from the river thanks to the walled-in garden (2); it was even furthermore separated from the Corderie and the river by the considerable property to the North of the garden that actually fitted into the grid pattern but in fact did not form a part of the section of the town here considered(7).

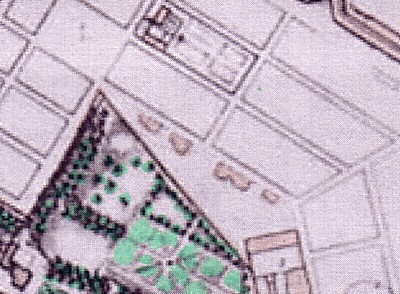

The 1688 plan tells us that this estate was known as 'Les

fonderies' - the foundry works.

The property opens not to the town but towards the Northern

ships' basin and, indirectly, towards the Corderie.

West

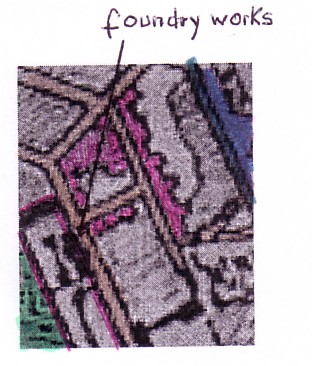

1688: The

foundry works (walled in adjacent to the 'royal garden')

1688: The

foundry works (walled in adjacent to the 'royal garden')

If we had been searching here for

a likely site of workers' housing, fitted into the in area next to the

Corderie, we would have been disappointed. For we we have discovered,

rather than an estate housing

Corderie workers, another employer

whose workers had to be housed somewhere.

But let us look at developments

regarding the relation between the Corderie and the jardin royal

in

some detail first before we return to the overall relationship between

the two employers mentioned (the Corderie and the foundry works) and the

Northern section of the grid patterned town.

The planning proposal presented by this 1666 plan execerpt shows not only the Corderie, construction of which had just begun. It also shows the terrains immediately West of this representative building that were to become the 'jardin royal.'(9)

1666

1666

The context of old chateau

(3), new chateau (1), Corderie, and future royal garden

This future (garden) use cannot be ascertained, however, from the 1666 plan. But in view of the fact that the plan of 1672 and subsequent plans all show the royal garden right behind the Corderie, it is likely that such a use was foreseen from the beginning.

The close connection between a costly and extremely representative

building by the river and the large garden behind it cannot be put in doubt.

Add to this the nearby "new" château (1) and the old

château (3), in ruins already, and situated partly in the royal garden

envisaged.

The foundry works are already indicated in 1666. Which

means they were either a project or construction had already started.

The 1672 plan reduplicates the pattern of the royal garden

foreseen already in 1666.

The Corderie (now already completed) and the foundry

works are indicated on the plan.

1672

1672

17th C

17th C

Plan in all likelihood drawn between 1672 and 1677

Shown in this fine plan (dated by us as pre-1677 and post 1672) , rows of trees and the park-like, walled-in lay-out of the large estate in the back of the Corderie (known as the 'jardin royal') underscore the representative and thus, 'royal' character of this area. We may well call this part of town which remains outside the grid pattern, the real 'ville royale,' as opposed to the 'ville bourgeoise.'

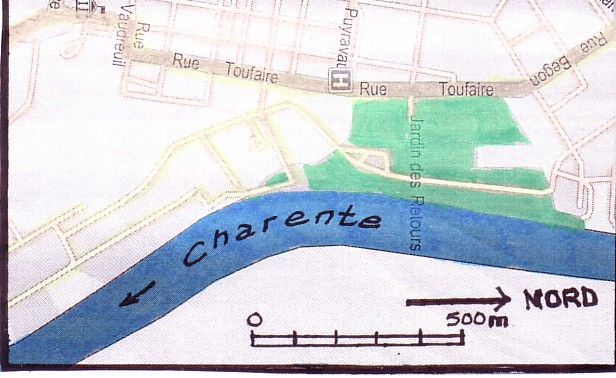

The core information for this part of Rochefort contained in the

pre-1677 plan

has been entered here into today's plan. The barrier function

of walls (those of the

jardin royal and the foundry works) is recognizable. The terrains

North of the

foundry constituted practically a 'backwater' of urban development:

terrains that

were not favorably sited

However, the exemption of the terrains in the back of the Corderie from the grid-patterned town was not unmistakably foreshadowed by the initial plan of 1666.

In the earlier plans, the future terrains of the 'ville

royale' (right behind the Corderie) can certainly be identified already.

But a clear lay-out of streets, including a wide main axis in a North-South

direction, was also visible. Only the tree-studded main North-South axis

and a much more narrow tree-studded street running in a North-South direction

immediately behing the Corderie have remained in the above 17th century

plan from the planning proposal (as shown in 1666 and again found

on the 1672 plan). The East-West streets of the street pattern have faded

into the remaining garden lands and have either been entirely wiped out

or turned into mere garden paths. Thus, the orientation of this garden

terrain is clearly a North-South orientation now. The East-West connections

of the 1666 planning proposal have been almost completely eliminated, drastically

reducing (or rather, eliminating) the "permeability" of the terrain for

East-West traffic.

West

1666

1666  post 1672, pre-1677

post 1672, pre-1677

If the initial plan was so determinedly revised

in this area next to the Corderie, weighty 'facts of life' must have collided

with the original planning proposal. We must not forget that except for

the Corderie, the area in question comprised the old, razed château.

It was, so to speak, cherished aristocratic land. The (by now walled-in)

estate that was realized here and that made impossible the execution of

the original planning proposal for this area, can only be ascribed to a

major (aristocratic) user or owner, perhaps the nephew of Colbert himself.

The fact that it is commonly referred to as the 'jardin royal' lends

weight to such a hypothesis. Of course, it was no more destined for the

personal use of the king than the Corderie royal. It was State property,

as was the royal navy, the royal arsenal, the royal foundry, and the royal

Corderie. But having a leisure function, high (possibly aristocratic) officials

must have enjoyed the use of it.

The 1688 plan confirms the function of the jardin

royal

as a barrier to East-West traffic and a representative extension

of the royal Corderie.

(4)

1688

1688

(1) (2) (3)

(1) Remains of the old château, (2) Corderie, (3) jardin royal, (4) the foundry works.

We have to note here, however, the houses shown also (though in a different way) in the pre-1677 plan on the almost triangular, elongated and narrow site immediately West of the jardin royal.

West

==> North pre-1677

==> North pre-1677

In the pre-1677 plan, all

the blocks to the West of the 'triangular' terrain (except for the

monastery of the

Capucins

two blocks further West) were still empty.

The ramparts can be seen in the upper right edge of this plan excerpt;

to the Northeast of the houses of the triangular 'block', we see part of

the foundry works.

As the rectangular property of the foundry works is a

walled-in property, we can almost certainly exclude that the triangular

block was an extension of the foundry property and that the houses

were additional ateliers. The hypothesis that these were in fact dwellings

is the most likely one. As we are able to show (elsewhere in this chapter)

that the 'best sites' for aristocratic and bourgeois dwellings in the newly

founded town of Rochefort were situated along the main East -West axis

departing from the 'new' château in the Southern part of the town,

we can perhaps rule out representative dwellings. But do not the large

gardens behind them speak for exactly such a character? And isn't the plat

(Grundriss) of the houses quite different from either small workers' cottages

or long and narrow tenement buildings, so-called 'casernes' ouvrières

[Arbeiter-"Kasernen"] ?

We must admit that our search for working class housing

appropriate to house thousands of workers in the new town of Rochefort

is rather frustrating.

But then of course plans need not always be accurate.

Have the houses on the earlier [i.e. pre-1677] plan (solid

and large as they apparently were) already been broken down and have they

been replaced by 1688?

For the plan of 1688 shows much more modest buildings,

lined up in a different manner very close to the wall of the jardin

royal.

These houses now look much more like workers' houses.

1688

1688

Workers' houses next to garden and foundry?

If they were present already (and merely inaccurately

indicated) on the earlier (pre-1677) plan, they are indeed older than the

houses that have sprung up just North of the foundry works

and that appear for the first time in the 1688 plan.

1688

1688

The same houses west of the garden and the more recent houses

to the North

(shown in scarlet red)

Here, it is especially the long row of houses on the Northside of the street just one block North of the foundry works that captures our attention and that reminds us of so many late 18th and early 19th century rows of workers' houses we have encountered.(10)

The above excerpt from the 1688 plan shows a tiny part of the jardin royal to the South of the foundry works, the works filling the block between the garden walls and the street North of it (it is a property also surrounded by a wall, as we have already noted), and various dwellings on the blocks North of the works that did not exist when the previous plan was drawn up.

The houses have been marked here

in scarlet red.

The long row of houses we referred

to has been realized on the Northside of what is almost a cul

de sac, or impasse now. Almost a dead and street, that

is, if it were not for the forked road leading to a town gate in the Northern

ramparts of Rochefort. What is remarkable here is that the axis has been

abandoned that once led from the royal foundry works straight to the gate.

The connection has been discarded despite the fact that it was (at least

on the plan of 1672) a part of the orderly grid pattern then foreseen for

this part of the 'bourgeois' town. Such an alteration is weighty

and quite remarkable and transcends the mere fact that the grid itself

has been revised various time in this area. Now, it has not only been revised;

it has been mutilated in the most severe manner.

What has come in between is an obviously 'partly unplanned'

or arbitrary production of housing that cuts across the foreseen grid and

wipes out an important connecting axis leading up the a gate.

Our guess is that the speculative production of workers'

houses urgently needed for the work force ammassed in adjacent works (the

Corderie, the foundry) as well as the Northern harbor basin constituted

a weighty 'fact of life.' Production of such housing must have been, suddenly,

an overriding concern. The beauty and order of the grid is sacrificed,

however. An element of chaos is introduced into this section of the town.

Our guess is that the order of the grid would not have been sacrificed

that easily in the 'better' (Southern) part of town. Nor would a crooked

access to an important town gate have been an option there. (Instead, an

important 'dual' axis leads to the the town gate which points West, in

the direction of La Rochelle.) Here, in the Northern part, such order is

lightly sacrificed. And the terrains East of the forked road mentioned

that is leading to the Northern city gate leave an impression of wastelands,

as if they were terrains used at best for the erstwhile storage of

goods that have arrived by sea and have just been unloaded from ships anchored

in the Northern basin.

If we briefly look now once again at the larger context of this part of town, a juxtaposition and short comparison of the relevant plans will help.

West

West

1672

1672 pre-1677

pre-1677

The six blocks (a) 1672; (b) pre-1677

The outline of the 6 blocks shown

on the 1672 plan has been preserved on the pre-1677 plan.

In 1672 this entire area included

not one block where construction of housing had at least started. (No partially

built-up areas.)

The post-1672 / pre-1677 plan shows

the hypothetical warehouses or 'caserne' next to the basin and adjacent

to the by now considerably enlarged foundry works. The block to the West

of it is empty, as is the area of blocks adjacent to the ramparts.

A street seems to lead (or at least

is envisaged) along the Westside of the warehouse or caserne complex to

the ramparts.

The central East-West axis of the

six blocks is interrupted and stopped by this 'Caserne' complex.

The minor South-North axis from

the foundry to the gate mentoned before is already stopping at the first

intersection; it doesn't lead anymore up to the ramparts. (Interestingly

enough, the street section [Straßenabschnitt] of the minor South-North

axis that is missing on the post-1672/pre-1677 plan is again introduced

in the 1688 plan, but in fork-like manner. On the other hand, the street

section preserved on the post-1672/pre-1677 plan is omitted on the 1688

plan .)

The hypothetically built-up area in 1677  1677

1677

The area built-up in 1677 according

to Maxime Lonlas gives us a real headache

.

As we read the plan of 1688, the

large block existing by that time that encompassed the 'caserne' or warehouse

complex, is otherwise covered only by a few houses. They are lined up along

the side street paralleling the small, partly abandoned South North axis

from the foundry to the gate.

If this is correct and if

we "antedate" this information, this would mean that in the 1677 plan,

the area left white is covered by houses and the blackened area is still

left empty.(11)

Despite the information provided

by Lonlas regarding the built-up area in 1677, we also doubt that the long

row of houses we identified on the East-West street next to the Northern

ramparts on the 1688 plan extends beyond the intersection of that

'quasi-cul-de-sac' with the forked street leading to the gate.

Whatever we may find on this terrain

to the South of the forked street does not make the impression of an orderly

built-up area in 1688.

In fact, the L-shaped (an inverse

_| , by the way!) course of the street next to the 'caserne' (or warehouse

complex) that the 1677 plan indicates, seems to have been abandoned in

1688.

Had it been realized at all , or

just planned?

What is conspicious is the large

size of the block that has been formed in 1688 West of the 'caserne'/warehouse.

What is also apparent is the need

for empty terrains, for storage space next to the basin that seems to be

provided in one form or other, close to the ramparts and the basin.

The area in the 1688 plan: A Brief Summary

(a) The industrial and (presumed) working class areas

1688

1688  today

today

The six blocks in 1688 and the same information entered on today's

plan

The area of what were (in 1672) six blocks that is

shown here once again in the plan of 1688 [surrounded by a red line]

has obviously undergone a loss of urban status, importance, and value (in

terms of land rent). If the tenement houses, among them a 'long row of

houses' (but there are additional ones, on the 2 blocks just South

of that 'long row') helped their owners to recoup considerable rental income,

due to overcrowding, this lucrative business is counterbalanced by the

apparent deterioration of other areas to a status of mere storage space

which would fetch the cheapest of land rents but was nonetheless economically

vital. (12)

(b) Public buildings

(4)

1688

1688

(1)

(2) (3)

(5)

As for the buildings indicated in black on

the 1688 plan, they seem to be public buildings. The author who has redrawn

this 1688 plan has indicated here (in solid black) (1) the new château,

(2)the old château, (3) the Corderie, and - of course

- (4) the foundry works. We may in addition point out the small building

to the West of the South Wing of the Corderie (between ((2) and (3)) and

the two others to the North of the Corderie already mentioned further

above (5): buildings which in a way must have belonged to it and which

may have provided additional ateliers, storage facilities,

and/or

accommodation for workers). And we must point out the large complex

(in black) close to the (Northern) ships' basin: was this accommodation

for the troops stationed in Rochefort to protect the city - in other words,

a 'Caserne'? Where these warehouses, instead, connected with the

port function of Rochefort? Either way, these buildings offered no likely

workers' accommodation.(13)

Footnotes

(1 ) Maxime Lonlas, in his architectural

and urbanistic study on Rochefort, has noted the differentiation of the

urban space (espace urbain) as well. See: Maxime LONLAS, "[Rochefort] Domaine

Historique: L'évolution de la ville [de Rochefort] d'un point de

vue architectural", in: http://rochefortsurmer.free.fr/hist_archi1.php

He suggests three different urban spaces: the

"arsenal" (referred to by the figure 1 on his plan; figures 1; 4;

5 on ours); the "ville royale" (though he does not use that term)

(figure 2 on his plan; here; 2; 7) and the "bourgeois town" (figure 3 on

his plan: here 3; 6). To quote him verbatim: There are "[t]rois grandes

parties de ce plan de 1672: L'Arsenal (1), le jardin du Roy (2) et la ville

(3)." (Maxime LONLAS, ibidem, p. 2 of 2) His terminology is

descriptive in the most immediate, phenomenological sense of the word,

rather than based on a socio-economic analysis.

We must emphasize here, however, that we owe

a lot to the fact that Maxime LONLAS discovered decisively important plans

in the archives. The plans of 1666, 1672, 1677, 1724, and 1845 have been

obtained as black and white scans from his internet-based urbanistic study.

Subsequently added colorations and the selection of excerpts are not the

respnsibility of Maxime LONLAS.

(2) We shall come back to this question and deal with it extensively further below.

(3) During the 17th century, the majority of the housing stock especially in small towns (in many areas of Europe, including England, Germany, the present Belgium, Northern and western France) consisted still of wooden houses: so-called half-timbered houses (Fachwerkhäuser). Only the more important public buildings and the houses of wealthy people (usually members of the urban patrician "aristocracy" and the commercial bourgeosie [strata which frequently intermarried and became inseparable in the important commercial towns] were executed in stone.)

(4) Cf. Part 1 of this chapter on Rochefort.

(5) The plan of 1672, with the "parties bâties ou en cours de construction" indicated as solid dark blocks by Lonlas, can seduce the reader, however, to arrive at the opposite conclusion. At least on first sight. We shall try to show that any such conclusion which is taking for granted a fast rhythm of production of houses within grid of the well-laid-out town is too optimistic, to say the least.

(6) In fact, we do not consider the extension

of the built-up area indicated by Lonlas on the 1672 as "small" (even if

the fact that the blocks were only partially filled with buildings is obscured

and 'overstated' by the visual representation which suggests, at first

sight, completely built-up areas).

But in comparison with the area indicated as

"built" or "under construction" on the 1677 plan, the built-up area

indicated in 1672 is small indeed.

As far as the 1677 plan is concerned, it does

not only tell us about the stage which the development of the grid-patterned

town had attained by that time. The 1677 plan is also important if we want

to study the development of the Western faubourg.

(7) As we shall show elsewhere in the chapter

on Rochefort, the triangular terrain has been ceded by the 'jardin royal;'

a comparison of plans shows that this must have

happened between 1672 and 1677.

(8) In 1672 we discover a brook or rivulet in place of the subsequent harbor basin.

(9) The terrains in question are indicated on the 1666 plan excerpt by their orange-colored street pattern.

(10) The term 'long row' [Lange Reihe] may of course be misleading. In the 18th century and early 19th century, it usually refers to standardized rows of tenement buildings. In the present case, the outline (plat) of the buildings, as depicted on the 1688 plan, gives no indication as to standardization. On the contrary, [small?] buildings of different sizes seem to form this "long row of houses"!

(11) Maxime Lonlas seems to have in general

a tendency to overstate (at least implicitly) the extend and speed of the

construction of the 'ville bourgeoise.' The 1672 plan on which he superimposed

information as to the extent of built-up or partly buiilt-up areas visually

conveys an impression of a rather solidly realized core of the Southern

town section. The 1688 plan indicates, however, how many gaps existed

on these 'built-up or partly-built up' blocks.

Also, if Lonlas suggests, by his reconstruction

of Rochefort's urban development, a fairly orderly development of the six-block

area in question (in the Northern town section), the development between

1672 and 1688 scrutinized by us suggests the opposite: a rather chaotic

development which is typical of the 'less-bourgeois areas of town': areas

of industry, working class housing, military barracks. Exactly the mix

we seem to find here! By the way, a 19th century plan of almost the same

area included in the otherwise commendable study by Lonlas shows that the

large complex next to the 'old' Northern harbor basin was indeed a 'caserne'.

On this 19th century plan, the _| - shaped course of the street that we

do not find to be realized on the 1688 plan, appears finally. Or was the

1688 plan inaccurate, in this respect?

(12) The military use of urban space in this area also went against the grain of profitable land use, to be sure.

(13) Indeed the use of the building complex

as a 'caserne' verified on a late 19th century plan may date back to the

late 17th century.

* *

*

We have up to now looked at aspects of the Northern part of the 'ville bourgeoise' in their interplay with the 'ville royale' (including the Corderie royale).

In the next part of this preliminary study, we shall look at the Southern part of the 'ville bourgeoise,' the 'arsenal proper' (surrounded by a canal or ditch), the area of the "ancien quai de commerce", and their relationship.

But before we wind up this part of our study, we show

here, again, the northern section of Rochefort, as foreseen by the original

planning proposal of 1666 and the especially graphic plan of post-1672/pre-1677.

West

1666

1666

Northern part of the grid-patterned lay-out, as planned

(plan of 1666)

West

N.B.:

1666 (redrawn)

1666 (redrawn)

We have redrawn the badly readable sttreet pattern, at the risk of making mistakes

Our copy of the 1666 plan is too bad to thoroughly compare changes

West of the garden royal that apparently must have occurred between 1666

and 1672 (or 1677).

All we can say here is that apparently quick connections to the

ramparts were thought to be essential in 1666.

The grid West of the jardin royal and the grid North of the jardin

royal overlap in places, which made for blocks that were rather small and

(of course) triangular, in the 1666 plan. Such blocks were difficult to

parcel and "market." A realistic adaptation was therefore warranted

and did in fact occur.

Another irritating feature of the 1666 plan is that to the West of

the jardin royal, the "street" pattern of this garden terrain and the continuation

of the grid foreseen for the Southern part of town do not coincide. Which

makes for strange effects of "interference" (Interferenz). In later plans,

the influence of the garden's pattern on the grid in the Northern section

of the 'ville bourgeoise' (that was probably - in part -

becoming 'proletarian', as have tried to show) is eliminated.

.