ROCHEFORT (PART III)

ROCHEFORT: A DETAILED DISCUSSION OF PLANS:

THE SOUTHERN PART OF THE 'VILLE BOURGEOISE' AND THE

ARSENAL

In the preceding part (Part II) we have tried to understand the relationship of the Corderie, the 'ville royale,' and the Northern part of the 'ville bourgeoise,' paying special attention to the development of what may have in fact become a working class neighborhood, close to the foundry works and the Northern harbor basin.

In this part of our study we shall look at similar aspects

- if they can be identified, with regard to the Southern section of Rochefort,

including the arsenal proper and adjacent terrains.

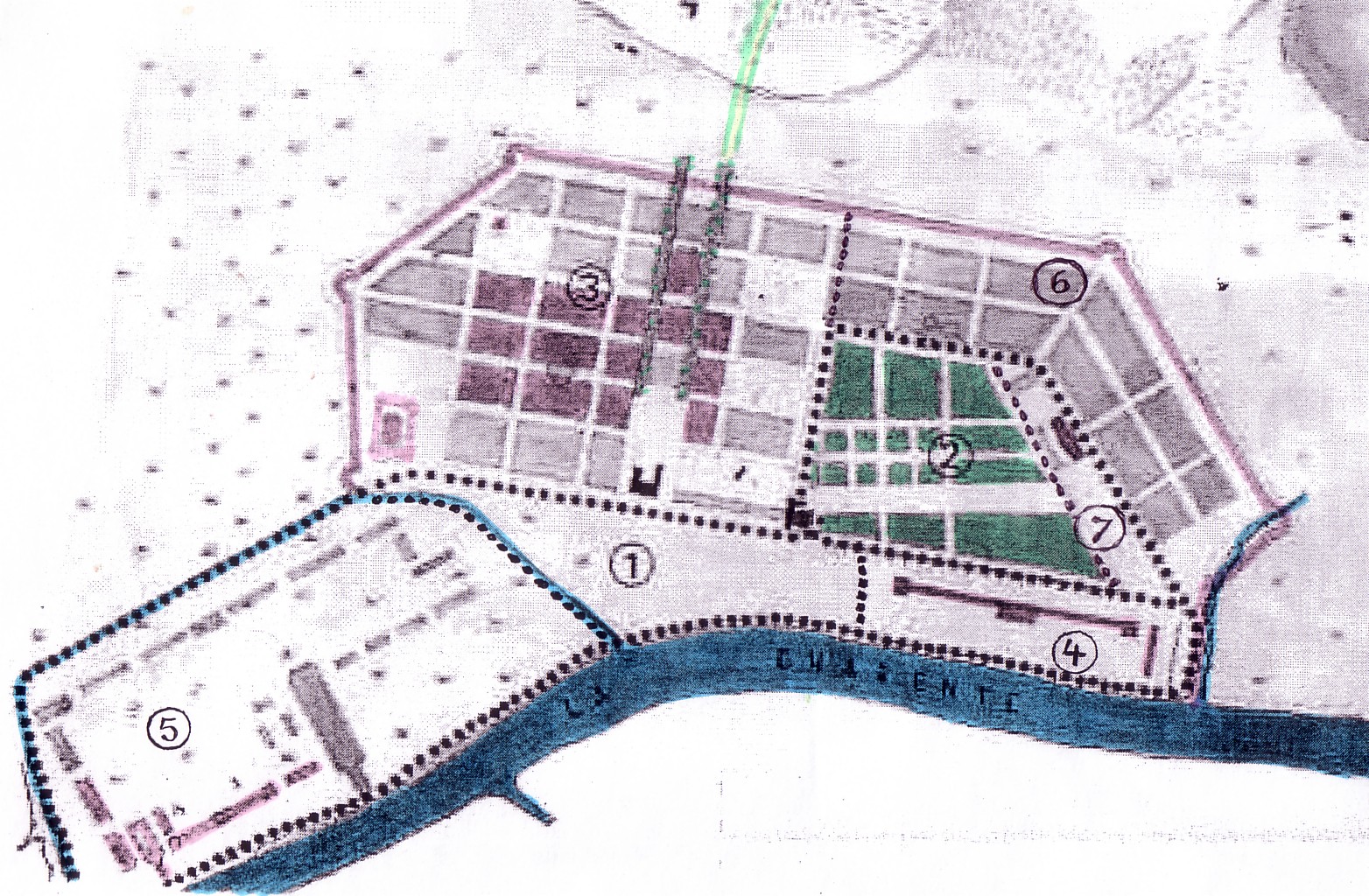

1666

1666

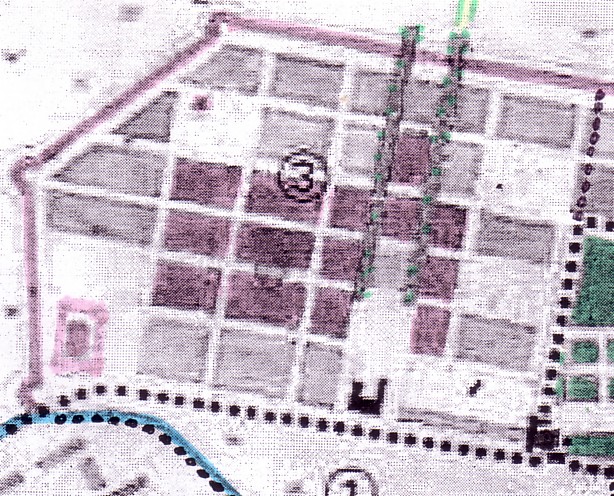

But before we turn to possible zones of working class housing, we will again quickly look at the entirety of the Southern 'ville bourgeoise,' moving from plan to plan and briefly commenting on aspects that seem to deserve attention,

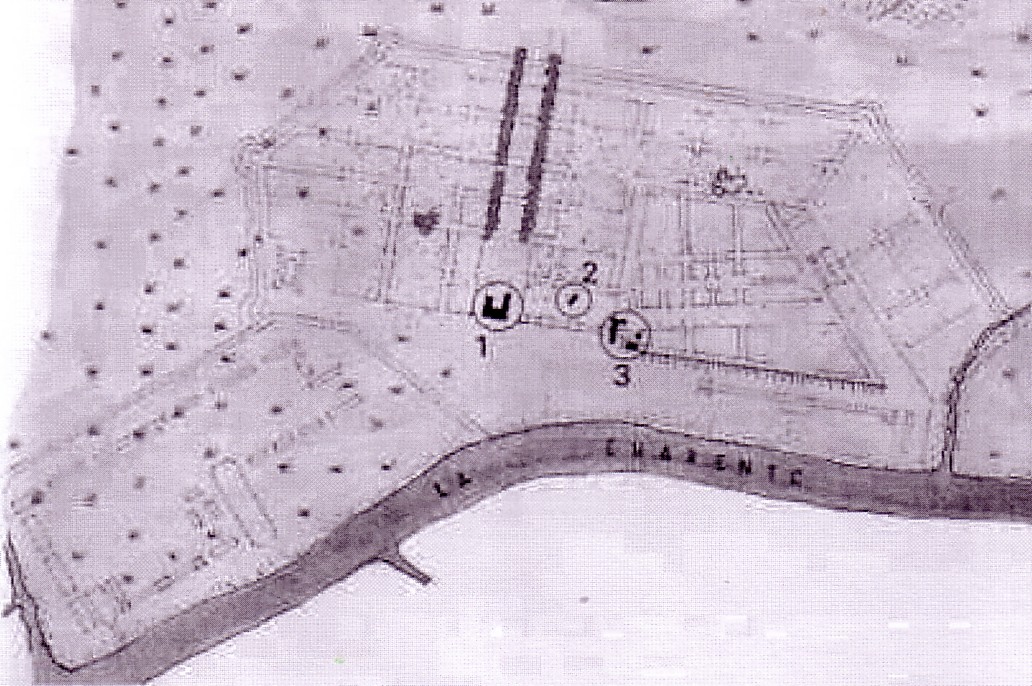

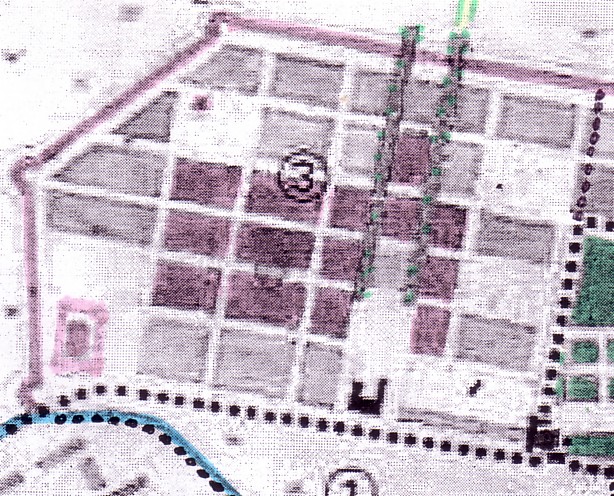

The above plan is again (because we have to keep it in mind) the original planning proposal of 1666.(1) But of course we need a close-up.

The following excerpt from the 1666 plan has been

colored only slightly. We have accentuated the powder magazine that has

been emphasized in the plan. (It is surrounded on its Eastside and Northern

side by a fairly large square.)

The 'impurity' a bit further to the North West may be

a blot; it may also be a natural feature (a small grove, perhaps).

The grid is visible but still not clearly.

West

1666

1666  pre-1677

pre-1677

Southern part of the grid-patterned layout, as planned (plan of

1666)

On the small pre-1677 plan, a red line indicates how we differentiate

the Southern and Northern part of the 'ville bourgoisie' (or "well-laid-out

town")

The following excerpt is easier to read. The streets have been colored slightly. The same is true of the trees of the dual East-West axis from the new château to the Western gate. The powder magazine is emphasized by stark red. A house (perhaps a pre-existing farm building?) is visible at a planned street corner a few blocks to the West of the powder magazine. Lonlas has entered into the plan the new château (the encircled black building, indicated by a (1)).

1666

1666

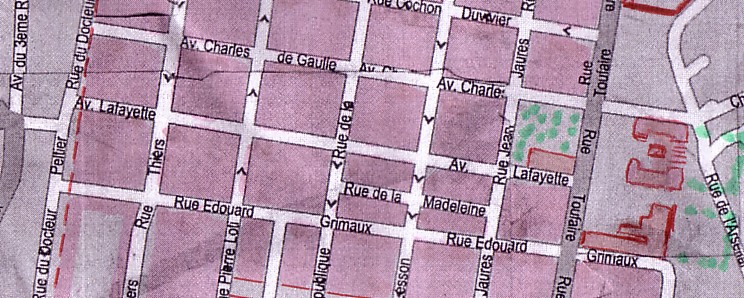

In this excerpt, an old axis running between today's Avenue

Lafayette and Avenue de Gaulle

has not been marked orange. It does not run parallel to

these two main streets and

disappears from later plans. (It is only faintly visible

on this copy of the plan. Cf. also foonote 4)

The strong prominence of the rows of trees lining the streets running westward from the new château cannot be cherished enough. By accentuating them in this way, Lonlas has given us a fine impression of the importance of the Southern town's main axis - a dual East-West (or should we rather say, West-East) axis, leading to the Western ramparts and obviously, a city gate.(2)

West

West

West  East

East

The backbone of the 'ville bourgeoise': two tree-studded streets 20 meters wide

Lonlas writes about these main streets of the 'ville bourgeoise',

"Two major streets (today the Avenue de Gaulle and the Avenue Lafayette), 20 meters wide, are 'doubled' by two other ones (today the rue Cochon-Duvivier and the Rue Grimaux) that are 14 meters wide. They take up the [old] axis from the hôtel de Cheusses [the new château produced after the old one was razed 40 years ago] to the church [of the parish Notre-Dame, outside the city-walls]" (3)

It is Lonlas who also points out the creation of three squares, not isolated [or cut off ("coupée")], as they would have been in the Middle Ages, but lined by roads." (4) One of them is surely the square West of the new château. We shall identify further rectangular greens on later plans but in fact do not find any additional 'modern' square on the 1666 plan. (The quare surrounding the powder magazine is exactly what Lonlas says the three squares were not: "cut-of" (coupée) or at least, partially cut-of from the 'ville bourgeoise." And rightly so, in view of the function of the building it did surround.)

The 1666 plan excerpt under scrutiny also lets us recognize the departure from the rectangular grid immediately North of the new château that was foreseen by the original planning proposal. The block next to Northern side of the château thus becomes even smaller than it would have been anyway had the grid pattern been maintained here. The block accentuated by an encircled building (which was inserted into the plan by Lonlas and marked by him as number (2)) is of course also affected.

We note something else: There is a street leading from the new to the old château and further on, as we may presume, to the Corderie... It is integrated into the grid pattern and at the same time delimiting the Eastside of the Southern well-laid-out town.

However, there is not necessarily

a street East of the blocks situated between the powder magazine and the

new château. Here, the grid-patterned town seems to fade into a sort

of 'no-man's land,' or empty 'waste land.' (The same can be said of the

square surrounding the powder magazine. It has no clear Eastward delimitation

but merges with the Eastern terrain adjacent to it.)

We shall come back to this fact

further below.

* * *

Let us proceeed to what might be a depiction of the next

stage of development: the plan of 1672. In 1672, as we know,

not only the Corderie but the Southern half of the atelier buildings of

the arsenal proper had been completed.

Lonlas also suggests that a large deal of the Southern

part of the grid-patterned town had been completed or was at least

in the process of being completed. (He refers to these blocks as built-up

or under construction.)

1672

1672

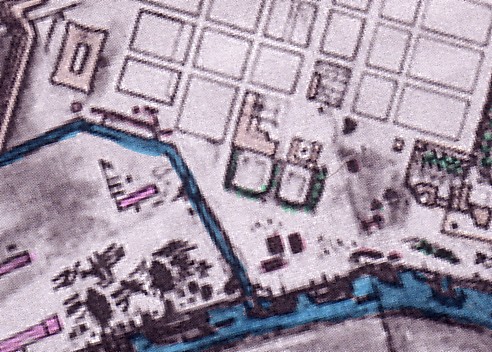

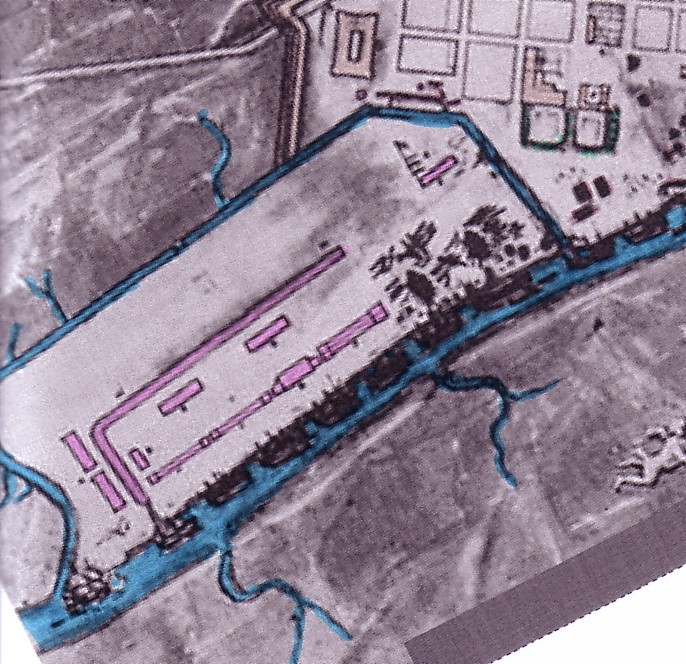

Plan excerpt showing the Southern part of the grid-patterned layout

as of 1672. (Superimposed on

this plan of 1672 is the information supplied by Lonlas

as to the 'parties bâties ou en cours de construction'.)

The details readable on the enlargement of the 1666 plan excerpt are not recognizably entered into this plan of 1672, or they have been blotted out when it was reworked and the built-up and empty blocks were indicated.

The two dark blots between the ditch or canal surrounding

the arsenal (which is situated towards the South) and the added figure

One (1) a little bit further North must not be mistaken

for houses.

They are symbols found also on the 1666 plan that probably

indicate grass land or 'marais' (swamps).

*

*

*

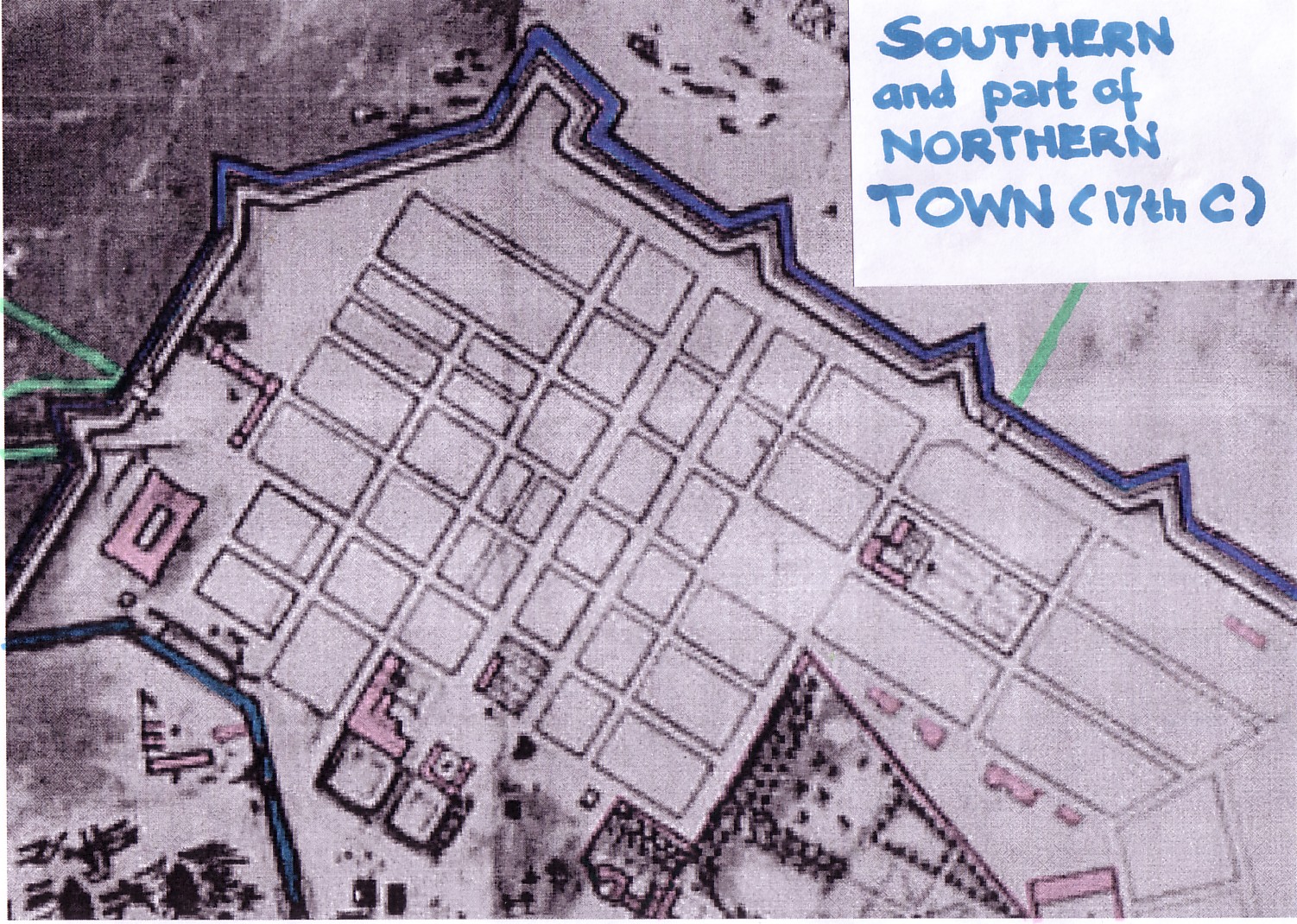

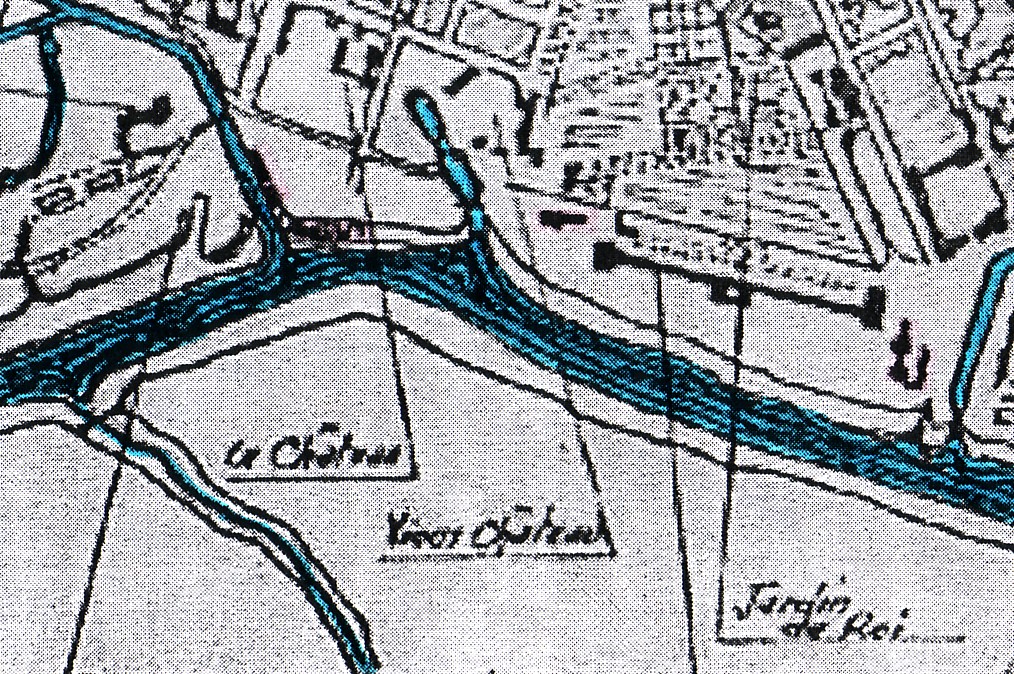

The pre-1677 plan also has to be considered, of course.

pre-1677

pre-1677

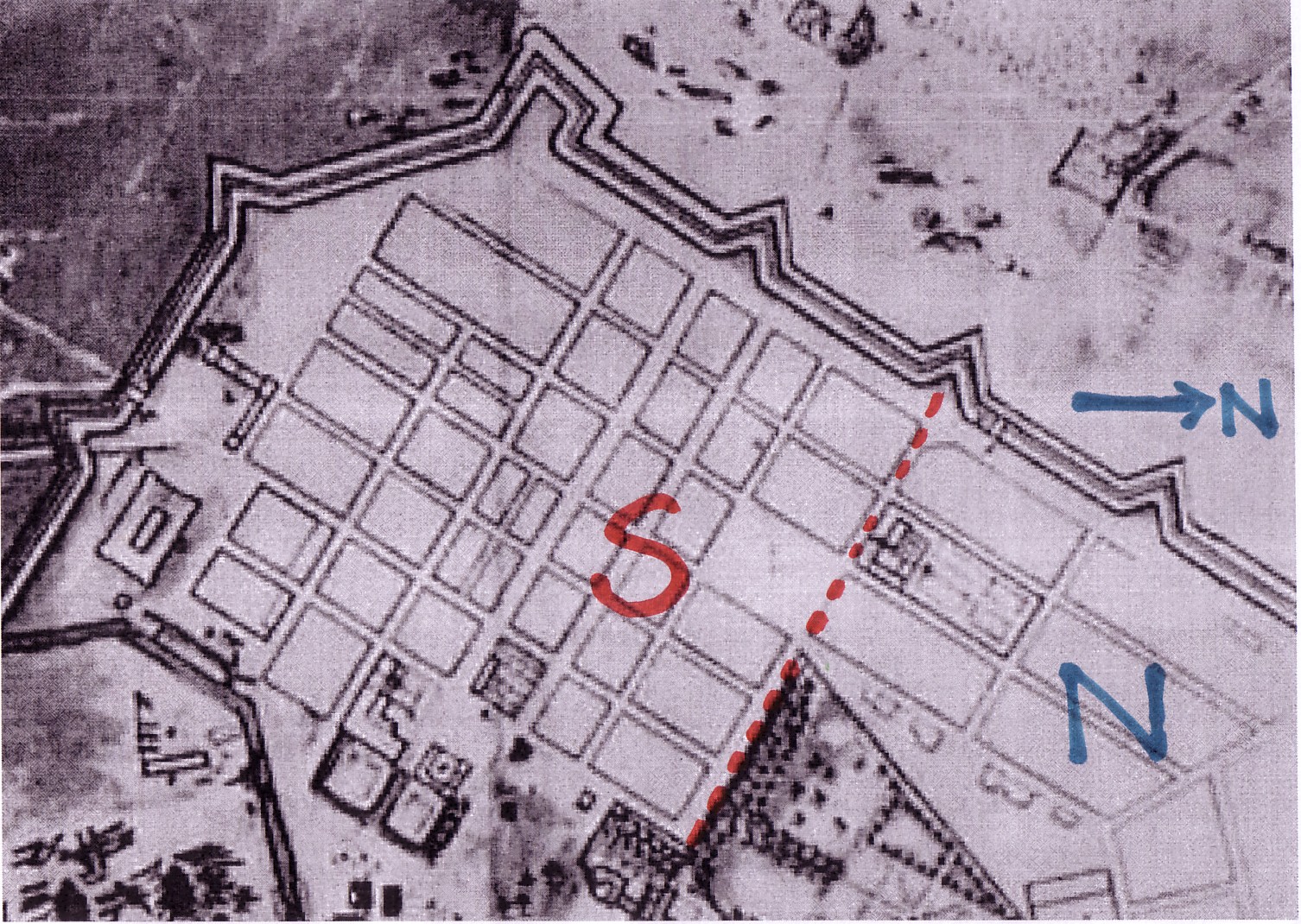

We have been able to date this plan as prior to 1677, and

post-1672.

Comparing this plan with the previous one, let us briefly reflect on the changes that affect the Southern half of the grid-patterned town as a whole.

What do we note?

The course of the Southern ramparts

has changed since 1672. Instead of three rounded 'bastions', we now discover

four V-shaped ones. The 'art' or technical expertise, regarding fortifications

is reflected by these changes. But they do not have to interest us in our

context, except where they have repercussions on the way the town is being

planned and realized.

Whether the changes of the grid

are in fact due to the changed course of the ramparts must remain undecided

for the moment.

What we can say however is that

the blocks close to the Southern ramparts that were not rectangular in

1672 have changed their form and are rectangular now. The space between

them and the ramparts thus has been partly increased. A rectangular form

of the blocks affected of course the subdivision (lotissement; Parzellierung);

it would provide for more rational, i.e. rectangular building

lots (parcels; Bauparzellen).

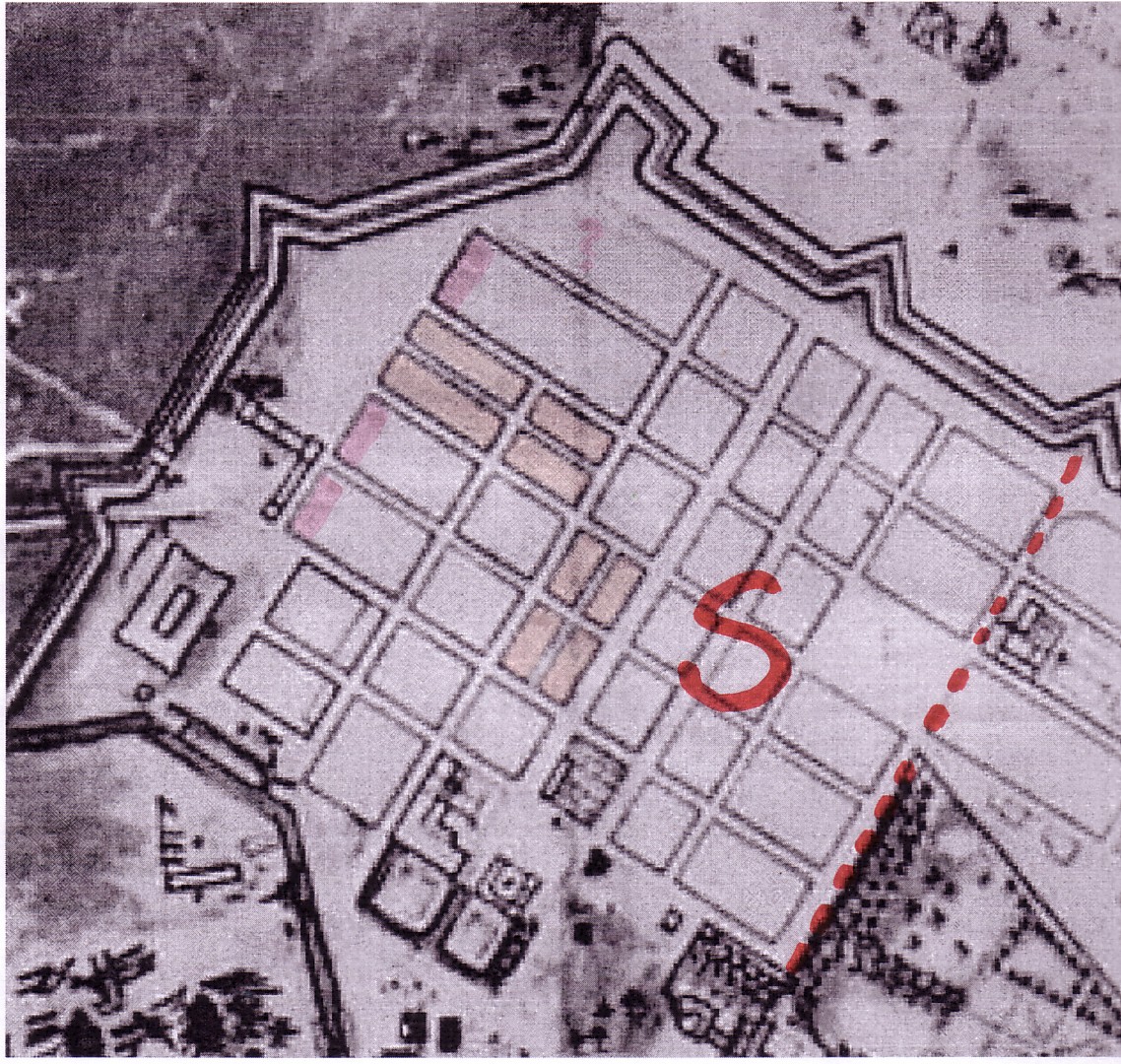

pre-1677

pre-1677

The blocks most decidedly subject to change

have been emphasized by color in the left plan

(pre1677/post1672) Compare, again,

the 1672 plan!

(But we note something else: Counted from

East to West, the width of the town adds up to 7 blocks on the pre-1677

plan [when not counting the subdivisions of the areas marked orange]

and to 6 blocks on the 1672 plan! This is obviously so because the Western

ramparts have been moved West by one block!)

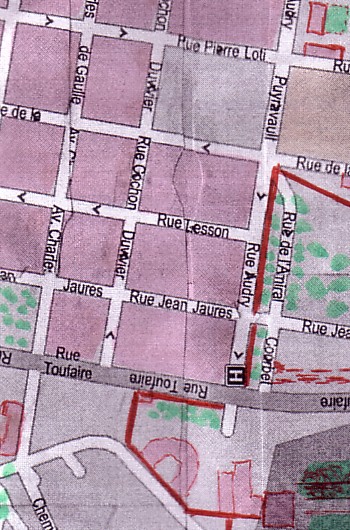

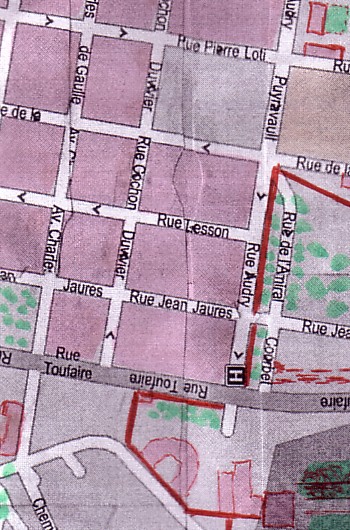

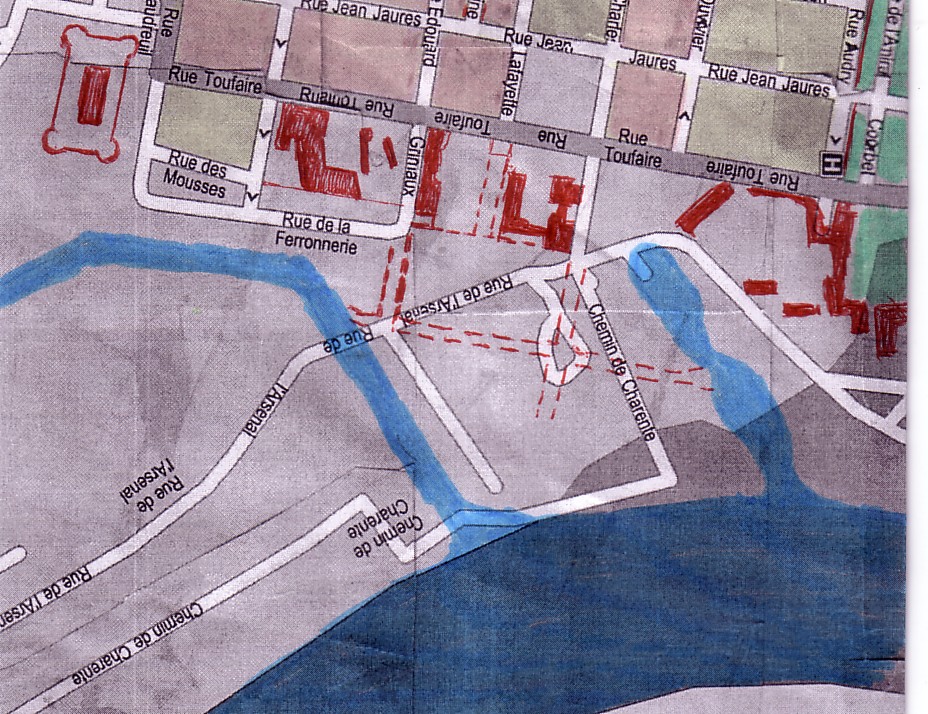

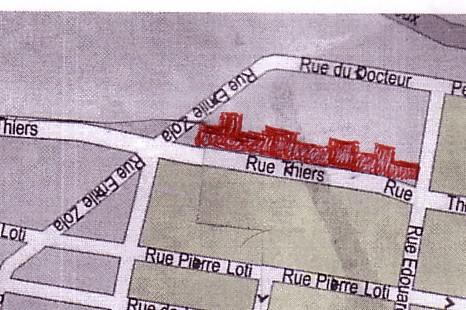

[pre-1677]

[pre-1677]

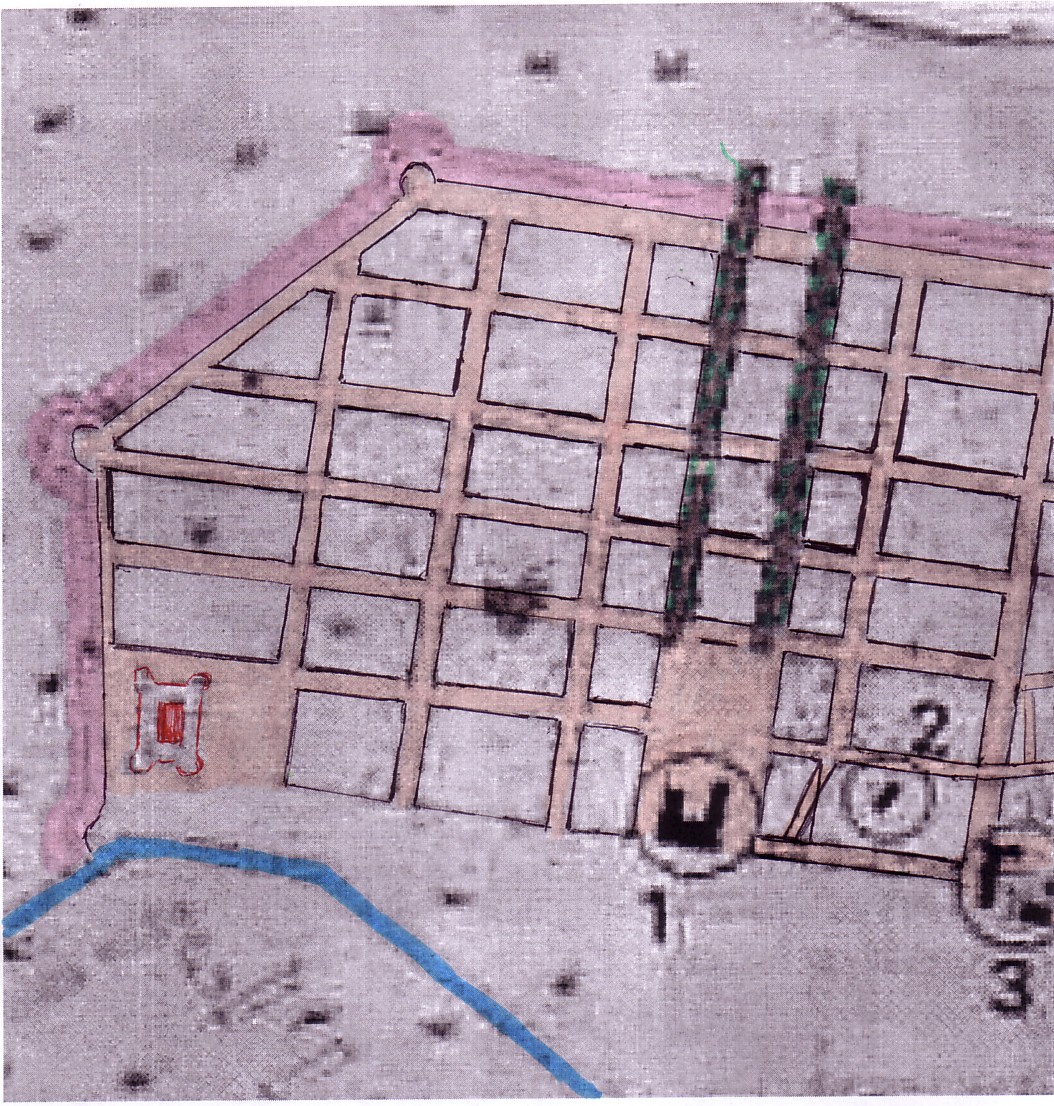

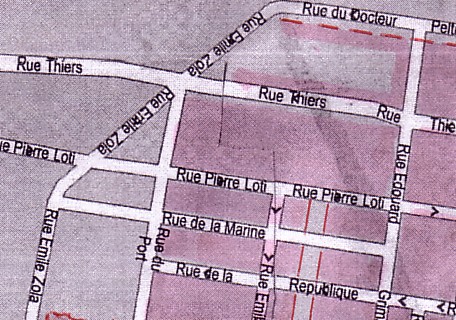

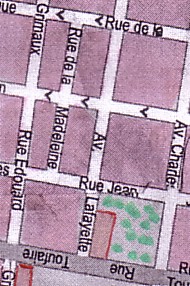

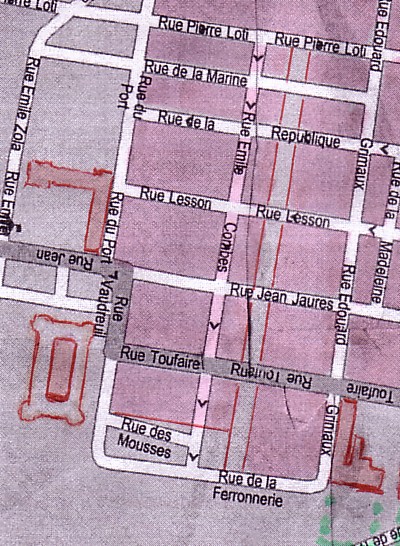

The features of the pre-1677 plan have been entered into today's

plan.

The block divided into 4 parts is bordered by the Rue pierre

Loti (W), the

Rue de la République (E), the Rue du Port (S) and

the Rue Edouard Grimaux (N).

Of the three large blocks in the Southwestern corner of the grid, situated to the West of the North-South axis that also touches the Western corner of the royal garden in the pre-1677 plan, one has been cut up into four small blocks. This would make, of course, for much smaller plots, to be given to less prominent and less affluent newcomers willing to build. Large building lots would require large houses which in turn would require more capital input, that is to say, wealthier builders.

[pre-1677]

[pre-1677]  [pre-1677]

[pre-1677]

new

château

park

The 2 blocks betweem Ave. Lafayette (N), Rue Ed. Grimaux (S),

Rue de la

République (W), and Rue Jean Jaurès (E) have also

been divided

Among the six blocks lined up in East-Westerly direction, along the Southside of the main East-West axis (an axis of two parallel, tree-studded roads, in fact), two have been cut up as well: by introducing a narrow alley, they have been effectually halfed. Here too, more modest houses were made possible in this way, especially on the sides of these blocks that did not touch upon the prominent E-W axis. If by this time parcels were sold rather than given away "for free" (as was the case, we are told, in the early phase when Rochefort's workers obtained 'lots' and 'construction wood'), this redrawing and shrinking of blocks must have reflected market pressures, anticipated or actual demand, that is. Obviously, a well-laid-out town could not exist only of large and exquisite townhouses, not even close to the major (representative, tree-studded) "dual axis" from the château to the Western gate.

If the grid pattern thus has been

modified quite a bit at some point between 1672 and 1677, many core characteristcs

have remained stable. Thus, with regard to the equally distanced North-South

streets, their distance has not been changed between 1672

and the situation on the later, pre-1677 plan.(5)

We can assess that because the 3 blocks just South of the royal garden

have not undergone any change but remained stable.

1672

1672  pre 1677

pre 1677  today

today

These three plan exerpts are again reproduced

below (enlarged)

1672

1672

The location of the North-South axis constituting the Western

border

of the 'jardin royal' in 1672 has not changed later, as the following

plan shows

post-1672/pre-1677

post-1672/pre-1677

The three blocks bordering on the South side of the 'jardin royal'

in this plan

are identical with those shown in the above 1672 plan

today

today

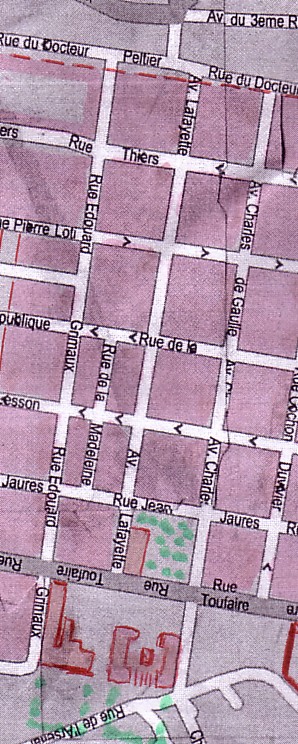

Several features of the pre-1677 plan have been entered into this early 21st C plan

In other words, it is the shortest

distance (via the Avenue Charles de Gaule or Avenue Lafayette) between

the Eastside of the new château and the North-South axis that is

touching the Westernmost tip of the jardin royal (in the pre-1677

plan) respectively forming the Western border of the jardin (in the 1672

plan) that has been kept stable.(6)

This distance is still made up of four blocks of equal width. And

therefore we can say that not only have the 4 main East-West streets of

the Southern 'ville-bourgeoise' mentioned by Lonlas remained in place.

But the 5 blocks which can be counted from the old chateau westwards to

the ramparts on the 1672 plan are still intact. If we now, in the pre-1677

plan, count one more block (6 instead of 5, counting from the old chateau

westwards to the ramparts, and 7 instead of 6 block, counting from the

block North of the powder magazine westwards to the ramparts, this is because

the Western ramparts have been moved West by one block.(7)

Otherwise, the grid is basically intact, except for the minor corrections

already mentioned.

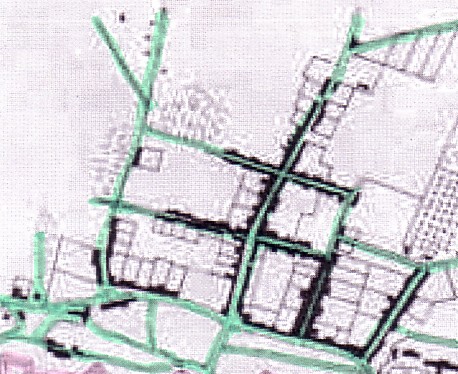

While the main East-West dual axis (Ave. Ch. de Gaulle; Ave Lafayette) is still in place and so is the minor East-West axis to the South (rue Grimaux) as well as the one to the North (rue Cóchon-Duvivier) of these two central streets, the two East-West streets closest to the Southern ramparts in the 1672 plans have changed their position in the pre-1677 plan.

This sketch shows the two east west streets

just North of the Southern ramparts

- The grid of the 1672 plan is presented in blue, the two 1672 streets

in turquoise (green), the

streets on the pre1677 plan in red

Small wonder if the course of the ramparts was modified, too. Or were there additional reasons for changing block sizes? Probably.

Several blocks South of the block

between the Rue Pierre Loti and the Rue de la République (that had

been split into 4 parts) were much larger in 1672 than they are a few years

later on the second (pre-1677) plan. Again, a diminuition of block

sizes in this area South of the central East-West dual-axis probably

amounted to nothing else than an adaptation to the market. Smaller blocks

meant smaller plots which in turn made for more modest houses with smaller

gardens in the rear. It affected, in all likelihood, the cost (if any)

of the acquisition of plots by private builders as well as construction

costs. The decrease in size of the blocks in question (Situated between

the Rue Edouard Grimaux and the Rue Emile Combes) meant of course

a shift of the Rue E. Combes to the North.

shift of the rue Emile Combes to the North in the pre-1677 plan

(details of pre-1677 plan entered into today's plan)

What is remarkable, however, is that this shift of the Rue Emile Combes to the North and the diminuition of block sizes between this street and the rue Grimaux was taken back again in the next plan (of 1677) and today's course of the rue Emile Combes is in fact that presaged by the plan of 1672. If the pre-1677 plan was not merely inaccurate, the transfer and transfer back of its location would indicate that few if any houses had been erected here in the years in question.

1677

1677

In the 1677 plan, the rue Emile Combes s again in the position

identified in thje 1672 plan.

Its Eastern prolongation continues in curved fashion and

leads up to the bridge crossing into

the Arsenal area.

Footnotes

(1) The rationality of the 1666 planning

proposal is, at first sight, striking.

To the South, the powder magazine and the adjacent

blocks of the grid pattern are facing the Arsenal. In the North, the Corderie

area is extended by what will be "the garden of the king." Just like

the grid-patterned town is confronting the arsenal to the South, it is

confronting the jardin royal to North (where the garden touches

upon three blocks of the rue Audry Puravault) and to the East

(where the garden and royal foundry are sited. East of the Rue de la République

and Southeast of the Rue Jacques Pujos). If the 1666 grid conveys already

an impression of rationality (despite the fair number of criss-crossing

streets in the Northern section), this rationality is especially striking

since the achievement of the second plan (1672). Now, the situation of

the completed blocks and the realization of the grid pattern appear 'perfectly

abstract' and 'rational'.

But is was already in the 1666 proposal that

most remnants (if they had existed) of odd and irregular houses

in the area had disappeared.

(2) As mentioned already in one of the

earlier PARTS on ROCHEFORT, it is Maxime Lonlas who has instinctively emphasized

this axis in the 1672 plan. He does not speak, however, explicitly of a

central

axis.

He has inserted this unmistakable dual axis (Doppelachse) because,

prior to the foundation of the town in 1666, he finds here "a dual

row of elm trees leading to the parish of Notre-Dame" ("une double rangée

d'ormeaux qui mène à la paroisse Notre -Dame") and because

he, too, cannot overlook the fact that the chevalier de Clerville who drew

up the 1666 plan "retained the château, the axis which departs

from there in order to lead to the parish of Notre-Dame, [and] an arm of

the Charente which seved as ditch" ["le chevalier de Clerville ... retiendra

le château, l'axe qui en part pour aller à la paroisse Notre-Dame,

un bras de la Charente qui servira de fossé."(Cf. Maxime LONLAS,

"L'évolution de la ville d'un point de vue architecturale", in:

http://www.rochefortsurmer.free.fr/hist_archi1.php)

That the elm trees were at once integrated into

the new plan meant more of course than simple respect for and insertion

of preexisting elements. If the new town was to have a representative

backbone or axis, trees that had grown already for a few decades were ostensibly

more valuable than trees just planted. They were an asset, and this asset

justified the fact that their insertion into the plan determined

both the orientation (or: alignment; Ausrichtung)

of

the entire new grid pattern and the concrete site of its main East-West

axis. In other words, what happened was more than preserving a rural

alley of elms, thus "retaining" the typical axis of a seigneurial estate

in the countryside. Something new was created: a major

urban

axis that made use of and thus exploited a pre-existing 'fact' without

preserving its character. This importance is of course recognized by Lonlas,

too, when he emphasizes the width of the four main streets running in East-Westerly

direction.

- The parish, by the way, is situated outside

the ramparts constructed since 1666. As for the new château that

was the obvious point of departure of the "row of elm trees" leading to

the parish further West, it too existed prior to 1666. It is described

by Lonlas as "une demeure presque neuve, celles des Seigneurs de Cheusses"

(an almost new dwelling, that of the Seigneurs de Cheusses). (Ibidem, p.

1 of 2)

(3) "Deux grandes rues (aujourd'hui avenues de Gaulee et La Fayette) de 20 mètres de large, doublées de deux autres (aujoud'hui rues Cochon-Duvvier et Grimaux) de 14 mètres de large, reprenant l'axe de l'hôtel de Cheusses à l`´eglise." (M. LONLAS, "L'évolution de la ville d'un point de vue architecturale: 1666 et 1672", ibidem.) - As for the "parish of Notre Dame" at a later stage (i.e., in the 18th century), cf. Robert FONTAINE, La Paroisse Notre-Dame de Rochefort au XVIIIe siècle. Rochefort 1993

(4) "Trois places seront crées, non pas coupés comme elles l`étaient au moyen âge, mais bordées par des rues." Ibidem)

(5) Only the block on which the new château is situated as well as the blocks South and (by implication, North) of it depart from this rule of sticking to equal width of blocks in the Southern 'ville bourgeoise,' a 'rule' which holds true for all the plans from the 1672 plan to today's plan (despite very minor pssible alterations made, especially in the ramparts area?). -We must explain here, by the way, why we take the 1672 plan as a point of departure. For one thing, our copy of the planning proposal of 1666 is not very clearly readable. On the other hand, it is readable enough to show that two grid designs overlapped inconclusively in the area just West of the future jardin royal. And furthermore,.they tentatively overlapped also in the Southern town in so far as the East-West direction of the streets to the South of today's Avenue Lafayette corresponds with the orientation of the later grid pattern but does not exactly correspond with the kind of East-Westerly orientation chosen between the new and old château - which somehow interfered (as a small, separate grid) with the larger grid, radiating into areas West of it. Thus, in the 1666 planning proposal, the three blocks South of the jardin were not properly rectangular blocks, it seems. The later rue Cóchon Duvivier was not forming angles of 90 degrees with the streets it was crossing, as far as we can tell from our copy of the plan. We have eliminated any consideration of the changes made in this respect between 1666 and 1672 from our above discussion.

(6) In other words: From the Southeastern

entry point into the jardin (where the Rue Toufaire meets the Rue Audry

Puyravault) [the rue Toufaire is practically identical with

the the Westside of the newly inserted addition to the park (covering

the area of the old chateau)] to the Westernmost tip of the jardin

(intersection of Rue Audry Puyravault and Rue de la République)

, we get again three blocks in both plans.

The entry of the orange-colored South-North park

lane [emphasized in our plan excerpt]. into the Rue Audry Puyravault (which

forms the Southern border of the jardin) is still the same:

a little bit West of an _| -shaped turn of the road as the rue Toufaire

turns West and is name rue A.P.. We can only conclude from the stability

of these features that the South side of the park and the total width of

the three blocks facing it have remained unchanged. And this not only between

the 1672 plan and the pre-1677 plan: rather, the three blocks that face

the South side of the park in the 1670s have remained stable in size and

location until today.

(7) It is quite obvious that the difference

of blocks counted in an East-Westerly direction (6 as against seven in

the later plan) is due to a Westward expansion of the town's plat by one

block.

By the way, we now also understand how the triangular

area West of the jardin originated that we discussed in another chapter

in the context of the Northern part of the 'ville bourgeoise': it has been

ceded by the jardin royal between 1672 and 1677. In the 1672 plan,

today's Rue de la République still forms the western border of the

jardin

royal.

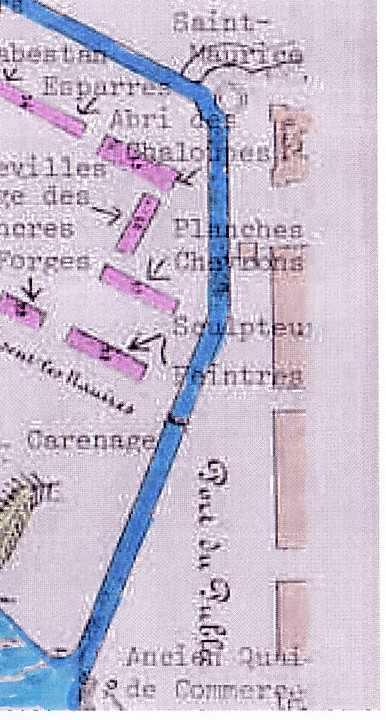

(8) On one of the plans of the arsenal,

published by Antoine Bourit, this area is referred to as the "ancien quai

de commerce." (Antoine BOURIT, "[Rochefort], Domaine èconomique:

2) Arsenal", in: http://rochefortsurmer.free.fr/eco_arsenal_1666.php, p.

5 of 6) That is to say, it is put out of use. Another source notes that

the location of Rochefort, before 1666, comprised the razed and new château

as well as an old landing site (apparently of minor importance, and used

to ship local produce).

* * *

The area of the "ancien quai de commerce" (the pre-1666 "port") and adjacent terrains

Looking for workers' houses by the riverside

In the course of this brief study

on Rochefort we have repeatedly asked us where the considerable work force

needed to build the Corderie, the arsenal proper, and the town found accommodation.

We also asked where the work force of the diverse large, State-run works

(that is to say, the employees of the Corderie, the foundry works, and

the ateliers in the ditch-surrounded 'Arsenal proper') were housed.

We have quoted the answer, taken

from historical documents, that workers came to this newly established

construction site respectively the newly operating works and obtained a

parcel of land and construction material (bois, i.e. wood) by a government

intent to attract them and keep them in place.

We have also shown a certain

skepticism with regard to the supposed implication of that hypothesis,

the implication that these workers obtained lots in the well-laid-out new

town, turing it, by way of their sheer numbers into a 'ville ouvrière.'

In our opinion, they were certainly marginalized, socially, at any rate, and spacially (that is, in terms of the urbain space allotted to them), as well.

It is Antoine Bourit who supports this hypothesis at least partially, or to be exact, with regard to the initial phase of Rochefort's development. While the Corderie and the first installment of ateliers in the arsenal proper were being built, while the grid pattern as devised was put in practice and the first well-aligned houses were being produced, makeshift workers' huts seem to have been banned from all or most of the the grid-patterned area of this well-designed new town.

In keeping with the social and spatial

segregation that separated the kings's palace and garden as well as the

new town in Versailles (which was made for aristocrats and members of an

extremely wealthy haute bourgeoisie) from the thousands of workers

entrusted with the travaux publiques of a grand royal project, here

too only the most miserly accommodation was accorded the work force.

The man in charge of supervising

the construction of Rochefort, Colbert de Terron (nephew of the royal minister,

Colbert), "had provisional collective dwellings [casernes ouvrières,

that is] constructed [for them] along the river", Bourit tells us, on the

basis, we may presume, of available historical records.(1)

This is exactly what we would have

inspected.

The site, desctribed only vaguely,

made sense. They had to be housed near the construction sites, and later,

near their work place.

But where exactly would we have

to look for these 'bâtments collectifs' (that according to Bourit

where merely 'provisoires')?

Bourit does not supply an answer.

No other source available to us supplies an answer. We can only attempt

to come up with a well-founded hypothesis.

What we know is that even in the early period, no workers' houses (provisional or not) are indicated on the terrain of the "arsenal proper." In fact, the ateliers, constructed or planned, would not have left much space for them. More importantly, the plans transmitted historically are so detailed in their depiction of certain buildings (the pre-1677 plan and the 1688 even detail the tree trunks and other construction wood stored in the "parc des bois" [Holzlagerplatz] of the arsenal) that it would be strange had they omitted workers's houses.

As for the workers of the arsenal proper, they had only one exit route from this well-guarded, ditch-surrounded work place: the bridge crossing the ditch or canal at its Northside.

And what do we find North of the

arsenal proper? Exactly: the former local port, referred to on one plan

as ancienne quai de commerce (out of use because ships anchored

in front of the arsenal proper and the Corderie and because, in addition,

new ships' basins were being built).

This is exactly the part of town

left without grid pattern. It is a part also devoid, until today, of buildings.

We always hear author refer to

the site of Rochefort as a swamp land ('marais'); we hear of the constructive

difficulties faced when the heavy Corderie building was being raised on

the unstable subsoil close to the river.

If anything constituted an urban

'waste land,' it was this area. If provisional "collective dwellings" were

erected for the workers arriving and deciding to stay in Rochefort, it

was here.

It must have been a particularly

unhealthy part of town, and indeed (as again Bourit informs us), a contemporary

of the 17th century developments in this area, Michel Bégon, is

known to have remarked that the town was the most unhealthy location in

the entire province.(2)

Obviously, the blocks of the

well-laid-out, grid-patterned town were too valuable to have them studded

with the wooden 'cabanes' of a working class population. Obviously the

design the authorities had in mind for this newly founded towen was part

'grand' and 'representative', befitting a 'ville royal,' part 'bourgeois'

and respectable, and of course, in this respect, adaptations to the facts

of life, realistic adjustments to their factual 'ability to pay' for fine

houses had to be made.

As far as the workers were concerned,

they were squeezed into areas no one else was keen to obtain, marginalized

sites, areas of town where they would be 'out of sight and out of mind.'

We have already pointed to sites in the Northern part of the 'ville bourgeoise',

"behind the foundry works" which may have been "good enough for them."

But here, in the swampy wasteland

close to the arsenal bridge, close to the previous 'landing site,' half

way between arsenal proper and Corderie, was in all likelihood the earliest

core of the 'proletarian Rochefort.' Its (early modern) 'proletaires'

were

housed, quite appropriately so, in casernes, just like the males

employed in Verviers woolen mills that found accommodation in the three

"casernes" of "les Grandes Rames" since about 1809-1810. Or the Fuerstenberg

manufactory workers who found accommodation in a "long row" of houses (Lange

Reihe) in the 18th century.

Among all the plans available to

us, it is the 1688 plan which most conclusively proves the existence of

'provisional structures' close to the river bank, in a site also well attainable

from the arsenal proper.(3)

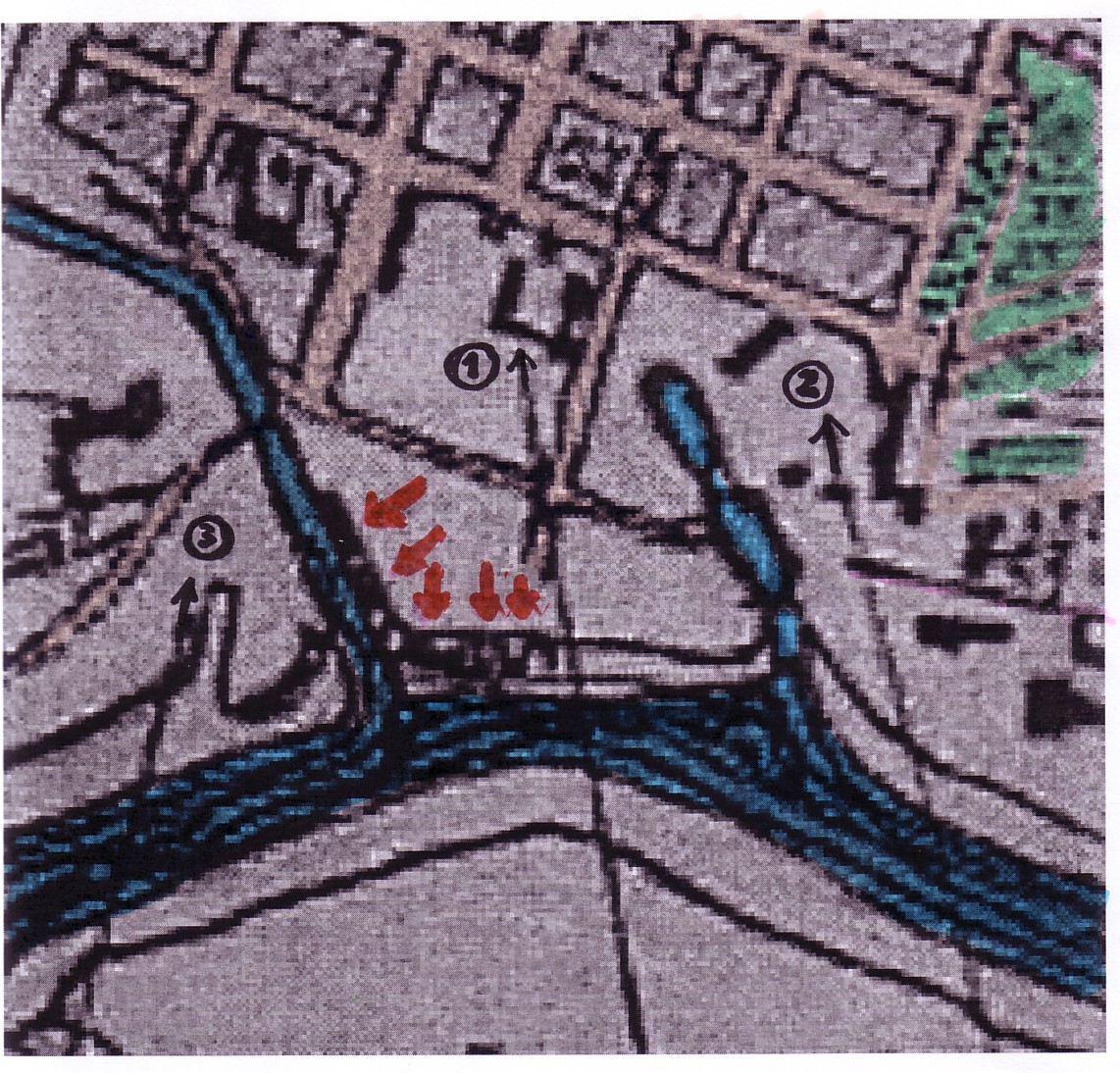

1688

1688

Suspected provisional workers houses erected (as collective

buildings / 'CASERNES' )

along the river bank, in the ares of an unhealthy marais.

These were obviously rather

large buildings rather than individual 'cabanes' (huts).

The structures are e,mphasized by red arrows. Also indicated:

(1) New château,

(2) old château, (3) "parc des bois" (wood storage

area of the 'arsenal proper')

enlargement (1688)

enlargement (1688)

In this enlargement, the buildings by

the Charente have been slightly redrawn

to enhance the readability of

the plan; we recognize a wall surrounding the

buildings which support the hypothesis

of aa 'casernement' of workers

Looking at another plan that is preceding the 1688 plan, we again find buildings here, next to the bridge leading into the arsenal, and close to the river as well as the ditch surrounding the arsenal. The plan incorporating such information is the "pre-1677" plan.

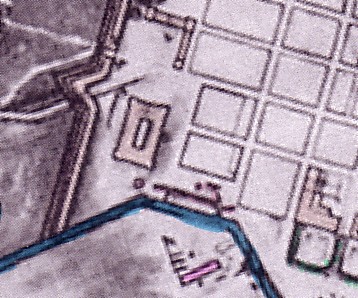

pre-16777

(post-1672) plan

pre-16777

(post-1672) plan

Three houses of considerable size are clearly identifiable in the terrain left otherwise fairly empty. They have been placed close to the site where the canal or ditch meets the Charente river

This plan very clearly shows three buildings put squarely on the 'wasteland' bordering on the old quai.(4)

What is astonishing though is that the subsequent 1677 plan omits all reference to buildings in this area.

Were the provisional houses taken down and built anew, in the manner shown on the 1688 plan? It would confirm the information regarding provisional buildings to put up the working class population by the riverside.

today

today

The former area between the 'arsenal proper', the grid-patterned town, and the Southern fringe of the Corderie. Various features of the plan drawn up in 1688 have been entered in today's plan. Blocks indicated as 'built-up or partly-built up' on Lonlas' version of the 1672 plan have been colored orange (other blocks are yellow)

If we look for further workers' houses near the river in the above 1688 plan excerpt, of course there are the buildings just South and immediately North of the Corderie that we have already suggested as possible workers' houses in the preceding part of this study on (Northern) Rochefort.

South of the C.

South of the C.  North

of the C.

North

of the C.

(2)= old château

(1)=Corderie [C, for short], (2)=jardin royal

(We have indicated the suggested

workers' houses on these 1688 plan exerpts by short arrows.)

Of course, in the light of Antoine Bourit's information that collective buildings for workers were produced by the river bank, our hypothesis that these buildings were also 'casernes de ouvriers' gains added weight.

But the houses pointed out next to the Corderie were of course not provisional buildings but important structures executed in stone.

In contrast to the houses close to the former quai de commerce, the buildings North of the Corderie appear both on the plan of 1677 and of 1724.

"pre-1677"

"pre-1677"  1677

1677

1688

1688  1724

1724

The house close to the Southern tip of the Corderie does appear on the "pre-1677" plan but may or may not be lacking on the 1677 plan.(5) It is then shown on all subquent plans starting with the 1688 plan. (6)

Apart from suggesting a possible mistake in dating the "pre-1677" plan and the assumption of an inaccuracy of certain plans with regard to such details as individual (even though major) buildings, we can still offer yet another explanation: that here today, a provisional structure constructed rather early on was subsequently broken down and replaced by a more permanent one.

If we take note of the fact that

in the case of the building in question as shown on the "pre-1677"

plan, its Southern tip is closer to the wall of the jardin royal

than its Northern tip while it is the other way round with later depictions

of a building in "this" location, perhaps the third hypothesis reflects

the likeliest course of events.

The 'elongated building' on the Northside of the Eastern section of the rue Edouard Combes

But there is yet another 'candidate': the elongated building on the Rue Emile Combes, to be exact on the Northside of its Easternmost block. Its location is among the most perfectly attainable, with regard to the 'arsenal proper,' the rue Emile Combes leading practically up to the bridge.

1688

1688

The elongated building on the Rue Combes is

marked by a short arrow. To the North of it we

see a wing of (1) the new château

The site of the 'elongated building' shown in the 1688 plan is however fairly close to the château. Was this therefore not a 'caserne de ouvriers' but an important building destined for aristocratic use or use as an office and dwelling of important administrators? If the location as well as the situation as shown in the pre-1677 (post 1672) plan seem to support such a possibility, another fact (that we will soon point out) speaks against it, however.

Let us first look at the plans that speaks against the hypothesis of workers' housing:

pre-1677

(post-1672)

pre-1677

(post-1672)

The post-1672/pre-1677 plan shows

here practically the same long building aligned on the North side of the

Eastmost block of the Rue Emile Combes; but it is not standing by itself.

It is forming part of a larger complex of buildings.

The court in the back of that we

take for fenced-in or walled in garden land would support a hypothesis

of non-bourgeois, in fact aristocratic use, as it resembles the courtyard

in the back of the neighboring (new) château.

What makes all these assumptions

questionable is that the appendixes to the elongated building (clearly

recognizable on the pre-1677 plan) have disappeared on both the 1677

plan and the 1688 plan. (The backyard seems to have gone as well.)

Does this not rather speak for

the hypothesis of provisional housing, thus in all likelihood workers'

housing?

pre-1677

pre-1677  1677

1677

While the pre-1677 plan shows an impressively large complex of

buildings on the block just South of the

château, the situation looks very

different only a few years later (in 1677)

The 1677 plan shows a much more

narrow building than the earlier plan, and the elongated building shown

is even longer than on the 1688 plan.In other words: While the pre-1677

plan shows an impressively large complex of buildings on the block just

South of the château, the situation looks very different only a few

years later (in 1677). But the situation keeps changing. Nothing is stable.

If the plans are accurate (which we must assume if we are to draw any conclusions

as to the kind of details here discussed), only one assumption can

explain this change: that ad hoc use was made of this bolock in the land

East of it, depending on urgent needs. One of the most urgent needs in

this early period was of course to provide accommodation for the vast work-force.

If our claim that workers' huts were not desired in the well-laid-out town

(and least of all in the parts crossed by wide representative streets),

then the choice of sites here identified becomes plausible.

In fact, the elongated building

on the 1677 plan is exactly the kind of 'long row' that we shall discover

again and again, in the context of early industrialization, in the 18th

and early 19th century. Even if no standardized house-types (executed in

stone) can be expected here at this stage of the Rochefort development,

the unimaginativee and cheap way of providing buildings patterned on the

'caserne de travailleurs agricoles' (often found on the large estates in

the countryside) can have been relied on here. It would presage later,

somewhat more advanced and certainly more permanent rows of workers' tenements.

For the sake of accuracy, we want

to point as well to the three parallel structures visible on the 1677 plan

only a few meters South of the narrow and long building under review.

These structures too proved to

be all but permanent. On the 1688 plan they are gone already.

However, the story of these provisional buildings does not end here.

1724

1724

As the 1724 plan shows, there is

a return, in concept, to what we saw on the pre-1677 plan: a larger, less

narrow compex of buildings has been realized by the end of the 1st quarter

of the 18th century, this time apparently more stable and in close connection

with the château. We would say that the pressing need to overcome

a shortage of workers' housing while avoiding large-scale settlement of

workers in the well-laid-out town has been overcome.

Why?

Because another way out has been

found by now: resettlement of arsenal workers in the western faubourg.

We shall come to that aspect of

Rochefort development a little further below.

But before we (very sketchily)

comment on it, let us summarize the findings with regard to likely workers'

housing in the 17th century.

(A) Workers were housed, as the

historical documents tell us, near the river bank. The arsenal area was

an area of work. Accommodation was not provided on these terrains.

The houses near the river that

we have to expect to have taken us workers are, in our opinion, mostly

situated on terrains we have described as a 'wasteland' more or less outside

the proper grid pattern of Rochefort. Others are situated just South and

immediately North of the Corderie.

The 1688 plan gives a very complete

impression of the structures in question. But we have to point out that

the exact sites and plats (Grundrisse) of the provisional houses situated

on or near the 'waste land' of the 'ancienne quai de commerce' are not

as stable as one might expect. Therefore, different late 17th century plans

show different locations. We have tried to follow up these 'minute changes'

with the help of several plans. (If the plans are not accurate, all this

comes of course to naught and what remains is the simple conclusion that

the houses were in fact situated on these terrains.)

Again, an excerpt from the 1688 plan, showing the discussed

sites of probable workers' accommodations

by the river (just North of the arsenal. just South

of the Corderie, and just North of the Corderie)

(B) Workers were housed, in all likelihood, in the neighborhood of the royal foundry works. (We have discussed this hypothesis in detail in the part dealing with the Northern section of Rochefort.)

(C) Workers may have also been housed

in other marginal sites of the town, most prominently on blocks bordering

on the powder magazine, and the block(s) near the Southwestern ramparts,

in the Southern town. We shall briefly look at these possibilities now

before turning to the (Western) faubourg.

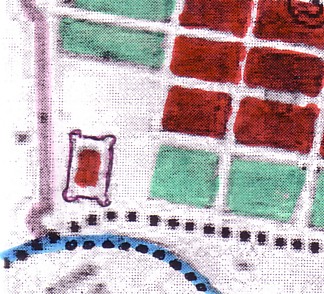

The area close to the Gun Powder Magazine

Lets us now focus on the area close to the powder magazine.

1666

1666  1672

1672

As the 1666 plans informed us already,

the Southern part of the well-laid out town was meant from the beginning

to comprise as its earliest structure a large building right behind the

ramparts - the State-owned gun powder magazine (shown in pink /red on

the 1666 / 1672 plan excerpts)

.

Lonlas gives us, on the 1672 plan,

an impression of the building process up to that year. His information

implies that the blocks next to the powder magazine (olored turquoise green)

were not even partly built-up by that time. In other words, neither

the area immediately adjacent to the gun powder magazine, nor the area

close to the arsenal ditch (i.e. the blocks marking the Eastern border

of the grid in this area), nor the zone close to the ramparts just West

of the powder magazine saw any construction of housing at all. With regard

to the first 6 or 7 years of Rochefort, we can thus exclude that this area

was being turned into a 'working class' neighborhood.

The "pre-1677" plan gives us no information with regard to the expectable construction process in this area, except that the establishment of a 'caserne' for the military West of the powder magazine can be ascertained.

If we compare the "pre-1677" plan and the 1677 plan, we note that the Eastern alignment of the block North of the gun powder magazine (formed by the Rue Vaudreuil, the rue Emile Combes, the Rue Toufaire and the Rue des Mousses) has been changed. The course of the Rue des Mousses in 1677 departs from the grid pattern; the angeles are larger respectively smaller than 90 degrees and thus its course is now slightly slanted.

We do not know which details are featured immediately East of the Rue des Mousses, between this rue and the Arsenal ditch. But the change of course affecting the street and specific activities here may be related.

pre-1677

pre-1677  1688

1688

In the plan of 1724 (shown below),

the slanted course of the rue des Mousses has been preseved.

In front of it, that is to say,

to the East, two tiny blocks have bren added. Likewise, East of the block

between the Rue Emile Combes and the Rue Edouard Grimaux, a narrow

block has been added as well.

These small blocks are somewhat

irregular in shape; they relate to the grid but don't form truly

a part of it. Rather, they can be described as a fringe area.

These blocks would not have been

formed without a felt desire to buid here, probably workers' houses, in

view of the proximity of the gun powder magazine and the very reduced size

of each of the three new blocks that have appeared by 1724.

A very small block size probably

translates into a high percentage of the ground of each plot being covered

by the respective building erected on it. In other words, we can expect

high densities which during the 19th century became even more typical of

working class neighborhoods.

On the 1845 plan, the three small

blocks identifiable in 1724 have been abandoned again. Were they too covered

by 'provisional' buildings?

In their place, we now find what

must be an elongated atelier, an extension of the ateliers found in the

Arsenal. In other words, the arsenal is expanding into the area we have

labeled a 'waste land' further above. Today's street plan refers to the

street that delimits the Eadternmost block of the grid in the East as the

Rue de la Ferronnerie, the iron works or iron foundry street.(7)

We may interpret this as a hint that the forges formerly arranged in the

Northwestern part of the arsenal proper has expanded considerably, turning

into a 'modern' iron work by (at least) 1845. As space for its expansion

could not be found within the terrains of the 'arsenal proper,' expansion

to the North of the ditch proved necessary and the ditch or canal

was abandoned and filled.

In view of the expansion of these

iron works just East of the Rue des Mousses and the Rue de la Ferronerie,

a bourgeois character of the adjacent blocks was even more out of the question.

On the block between the rue Grimaux,

Rue Toufaire, and the new château, the structure found in the

1724 plan changes its form again: it becomes much smaller than before.

A reflection of its changing purpose? The château becomes even more

than before (when it formed the border between the 'well-laid-out town

to its West and North, and the 'waste land' to the East) the delimitation

between the 'ville bourgeoise' and types of land use anathema to any 'bourgeois

(quarter of) town.'

1724

1724  1845

1845

The three small block close to the arsenal

The expanded arsenal ("ferronerie")

Today's grid pattern and features of the "pre-1677" plan (left)

and 1688 plan (right)

(Our hypothesis, articulated further above, that the Rue E.Combes

was at some point moved North and then back again is perhaps debatable.)

What is noteworthy is that in today's plan, the so-called "waste-land"

of the 1670s and 80s is still outside the grid

The Southeastern area close

to the ramparts

1672

1672

The 1672 plan excerpt showing the

Southwestern area close to the ramparts contains the information offered

by Lonlas with regard to blocks not covered by any buildings (turquoise

green) and at least partially covered by buildings (red).

pre-1677

pre-1677

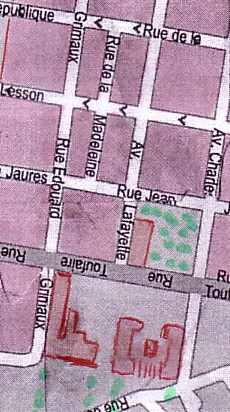

We have discussed already (further above) the subdivision of what is the 3rd large, elongated block when counting Eastwards from the Western ramparts.It is now formed by four much smaller blocks.

We have also mentioned that the

Southern aligment of the three blocks in the Southwestern corner of the

town has been rectified. These are rectangular blocks now. That they were

not subject to any building process up to at least 1672 has been mentioned.

In other words, no housing for the subaltern classes was produced here

in the 1666-1672 period right beneath the ramparts.

1677

1677

The block in the Southeastern corner of the town, with a row of houses along today's Rue Thiers

In the 1677 plan, we see a decisive

change: the building process seems to have made considerable headway. If

Lonlas is to be believed, the overwhelming majority of plots on most

blocks in the Southern 'ville bourgeoise' has seen houses spring up. In

view of the fact that little more than a decade has passed since the planning

proposal was formulated as a drawn-up plan, this would be truly astounding.

Though we have some reservations, let's not dispute the assumption of Lonlas

here.

What counts is that Lonlas finds

a row of houses on the most Southwesterly block of the toen, right beneath

the ramparts, and this finding is indeed confirmed by the plan of 1688.

1688

1688

The part of town under review, as shown on the plan of 1688. The row of houses is again pretty visible

Any such row of houses, close to

the ramparts, would qualify nowhere in Western Europe at the time as a

bourgeois neighborhood. We depart from the premise that these must be workers#

houses indeed. The transfer is beginning to be felt that will end up by

a relocation of Rochefort's work force from 'terrains malsains' close to

the Charente (in the Easternmost part of the town, its "wasteland" between

arsenal and Corderie [respectively the fringes of the Corderie, mentioned

above, as well])to the West, both inside and - above all - outside the

walls.We shall come back to that in some detail below.

1688

1688  today

today

The information of the row of houses referred to has been (very approximately) enterted into today's plan

1724

1724  1845

1845

We refrain from commenting

here on the plans of 1724 and 1845 as they do not add any information beside

the fact that over time, the area of the block in question was filled with

houses.

The character of the neighborhood

will hardly have changed because of this in the years mentioned.

A similar neighborhood for the 'subaltern

classes' in all likelihood was produced on the triangular block to the

Southeast of the long row of houses just referred to, and on a small, four-cornered

adjacent block that is not rectangular, however. An even smaller, very

narrow block is added to its East on the plan of 1845. This neighborhood

is pretty close to the caserne shown on the 1688 plan that seems to have

'disappeared' by now. A square may have by now originated between the rather

small blocks we have commented on and the gun powder magazine. It may have

served as a market. Situated close to the ramparts, it would have to be

considered closer to 'medieval' designs than to modern ones, except for

its rectangular shapes. In other words, it is marginalized rather than

well-integrated in a (typically bourgeois) quarter in order to 'beautify'

it. Its purpose would therefore be functional trather than aestheric. in

keeping with the area as a whole (powder magazine, terrain of the former

military 'caserne', surmised workers' houses).

Footnotes

(1) As Antoine Bourit puts

it, "Colbert de Terron fit construire des bâtiments collectifs, provisoires

le long du fleuve pour y 'camper' la population." (Antoine BOURIT,

"[Rochefort] Domaine Économique. La ville nouvelle", in: http://rochefortsurmer.free.fr/eco_villenouvelle_1666.php,

p. 1 of 2) Bourit does not specifically speak of workers, just of "the

population" (which of course consisted initially above all of workers).

He does not elaborate on the significance of his information, nor does

he point out an exact location of these "collective dwellings."

Antoine Bourit's information is corroborated,

however, by a document that Maxime Lonlas seems to rely on

when he states that with the apparition of the "faubourgs," houses

existing "close to the arsenal" ("à proximité de l'Arsenal")

were sold by workers to "officiers du Roi." We have to keep this in mind.

Where if not close to the work place would we have to look for initial

workers' housing produced after 1666?

The siting of the workers' houses, the subject

or agent [Träger] of production (Colbert de Terron, that is to say,

the government), and the way of their producion (makeshift, provisional,

designed as "bâtiments collectifs") all seem relevant to us, in view

of a central question focused on in this study that researches the effects

of early industrial ensembles, with regard to the production of workers'

houses.

(2) Ibidem

(3)Any attempt to locate workers' houses

in this area has of course to face the question why it starts with the

1688 plan if there are earlier plans to look at.

The plain answer is, because it is such a vivid

and detailed plan, and because it hasn't been reworked in order to indicate

built-up blocks (on a basis we cannot countercheck at the moment and in

a way which we suspect to involve too much optimism as to the speed and

extent of construction in the newly founded town).

As far as the earlier plans are concerned, the

1666 planning proposal obviously cannot tell us anything about (provisional)

workers' houses. It foresees merely those installations which would be

vital for a Navy yard dedicated to production and maintenance.

The 1672 plan informs us only about the built-up

and partly built-up blocks (an assessment we owe to Maxime Lonlas). The

details we are looking for cannot be found on this plan, as adapted to

its special purpose by Lonlas.

The only plans prior to the plan of 1688 that

we can rely upon for the purpose of a detailed comparison are therefore

(a) the post-1672/pre-1677 plan and (b) the plan of 1677.

(4) On the "pre-1677" plan we see the 'parc

des bois' at the Northeastern edge of the Arsenal which is also given on

the 1688 plan.The bridge is not indicated. On the other side of the ditch

or canal, to the North of it, a large empty terrain is visible South of

the well-laid-out toen.The powder magazine is visible to the West of the

forge. The adjacent blocks have not been occupied so far.

The terrains we have referred to as a "wasteland"

outside the grid are partly occupied .It seems to us as if a garden-like

court in the back of the new château and a similar yard in the back

of the building immediately South of it have been created. (In the 1688

plan this area is surrounded by pathways: a halfhearted, makeshift continuation

of the grid.)

Further East of these large, tree-studded backyards,

between the Easternmost pathway and the river, the 'real wasteland' begins.

And here we again discover buildings - though not exactly in the

same location as in the 1688 plan: They are three structures in all, each

of them undoubtedly pretty large, and certainly close to the river, a fact

that would correspond with the claim that Rochefort (at least for many

of its workers) was an unhealthy place: "the most unhealthy place in the

province." (In the words of Antoine Bourit: "A cette période, la

ville est le lieu de la province le plus malsain, selon les paroles de

Michel Bégon." [A. BOURIT, ibidem])

The interesting thing is that on this plan drawn

up "before 1677", the houses pointed out are not exactly

in the

location of the structures discovered on the 1688 plan.

This allows for two possible readings. Either

these were indeed very provisional buildings. Or the plans, in such

matters, weren't too exact.

Both plans corroborate, however, the existence

of large buildings close to the river bank in this area which nobody seemed

to have much use for.

Of course we must admit another possibility:

i.e. the not totally excludable reading that these were warehouses.

But at least the 3 buildings on the pre-1677 plan are not lined up nicely

like warehouses along a ship's basin or quai. The hypothesis that they

were workers' dwellings seems more plausible. If historical documents

inform us that "collective dwellings" to house [part of?] the work force

were constructed "le long du fleuve" [along the river], these structures

may have been such dewellings.

(5) We cannot read the 1677 clearly enough. The excerpt shown has been colored by us to emphasize what may be the building in question (just South of the Corderie). But was a building shown here, or rather a stretch of road that we mistakenly colored?

(6) Do we have to revise our assumption that the undated 17th century plan was drawn up later than 1672 but earlier than 1677? - We came to this conclusion because the 1677 plan was showing features not included in the "pre-1677 plan" but included in the 1688 plan. No matter how we approach these observations, we will be stuck with a problem.

(7) Alain DURAND, Les anciens noms de rues

de Rochefort. Rochefort (A.R.C.E.F.; Soc. de géogr. de R.) 1995;

cf. also Robert ALLARY, Histoire des rues de ma ville: Rochefort (Charente-Maritime).

n.p.[Rochefort] 1977. [We also want to point out here the publication

edited by the A.R.C.E.F., Une rue de la ville maritime au XIXe siècle,

la rue des fonderies à Rochefort (Rochefort 1995) which probably

concerns a street close to the old 'fonderies royales' in the Northern

part of town. As shown in another PART of our CHAPTER on ROCHEFORT, this

area must have developed into a working class neighborhood, as well.]

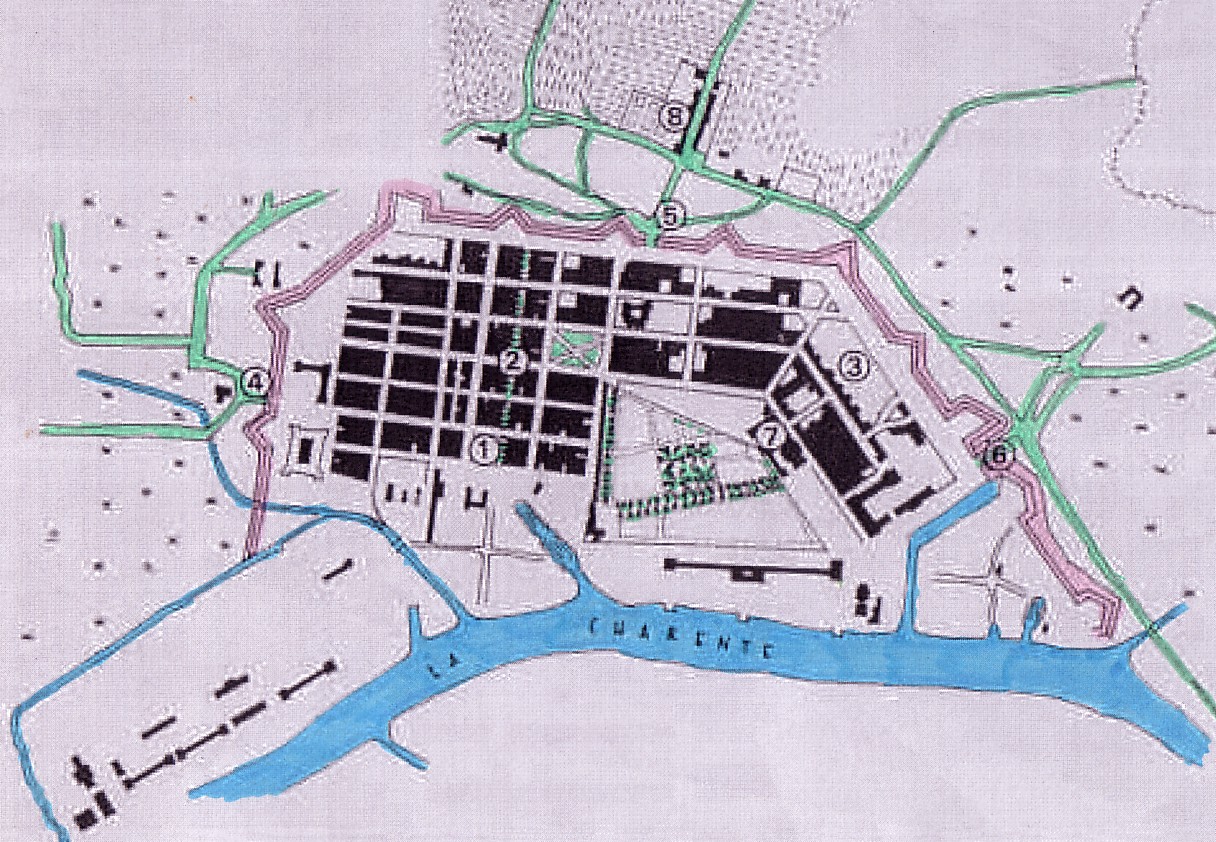

The Western faubourg

The Western faubourg: either a large farm or a hamlet (perhaps

the parish of Notre-Dame?) is indicated by Lonlas by way of

a "4"

The planning proposal of 1666, again

reproduced above, shows only one distinctive settlement beyond the future

ramparts. Although we know that there existed the 'paroisse Notre-Dame'

(the parish of Notre-Dame: that is to say, a church with (in all likelihood)

a few 'cabanes' of peasants, formerly subject to the Seigneur de Cheusses),

we cannot say for sure whether the settlement or farm indicated on the

above planning proposal of 1666 is in fact this parish.(1)

The next plan on which Lonlas inserted

information as to built-up and partly built-up blocks (in 1672) gives us

no information on the faubourg(s), which is why we turn now to the post-1672,

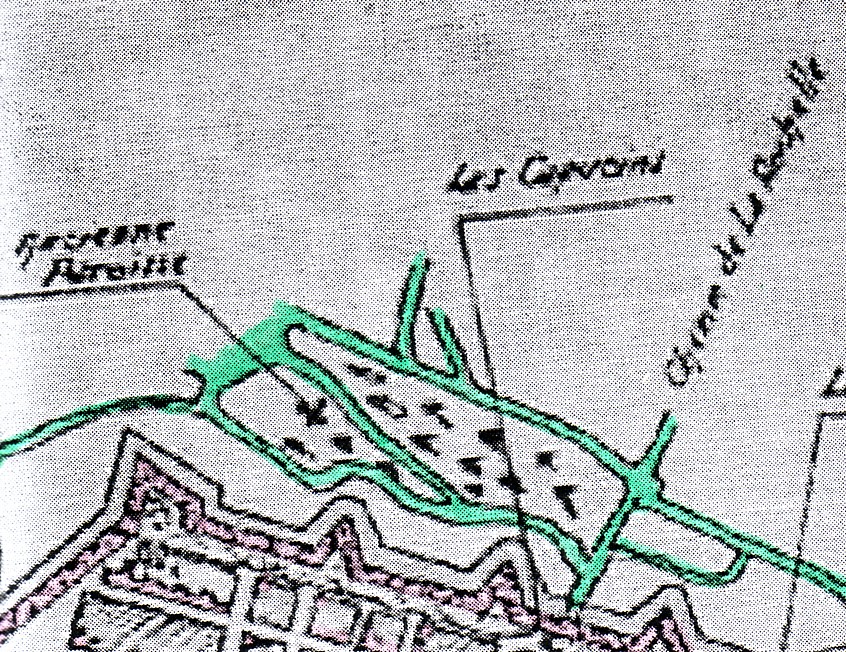

pre-1677 plan.

Here we seem to see the estate

shown on the 1666 plan in some more detail. It seems to be walles; it seems

to comprise several rural houses; there also seems to be a small grove.

It is situated next to the "chemin de la Rochelle", the track (or 'piste')

leading to La Rochelle.

A parish church ("ancienne paroisse") entered on a later plan further South, but closer to the walls, is not shown in this plan.

pre-1677

(post-1672)

pre-1677

(post-1672)

1677

1677

The 1677 plan shows the location

of the "ancienne paroisse" as a cross- [ ---|- ] -shaped

building. (The term appears on

the 1688 plan.)

The settlement shown in the

1666 in pre-1677 plans next to the "chemin de la Rochelle" has sensibly

expanded. (It is indicated by Lonlas by the figure "8".)

There are 4 other houses by now

in front of the ramparts, one close to the church of the 'ancien

paroisse' (ancient parish), and 3 a little North of the estate which is

situated by the "chemin de la Rochelle"...

1677

1677  1677

1677

The two nuclei of faubourg development shown on the 1677 plan

What would be important to understand

is the concrete dynamics of faubourg development to the West of the ramparts

that occurred between 1677 (when only the "beginnings" of a new dynamics

can be sensed) and 1724 when the faubourg has already grown to considerable

proportions.

As we have no data available which

would allow us to sketch that development and its individual, very specific

steps and characteristics, we can only point out a remarkable qualitative

trait of the early development of the faubourg in question.

At some time in the late 17th or

early 18th century, arsenal workers who possessed houses close to the arsenal,

sold these 'maisons' to 'officiers du roi'. They did so "in order to establish

themselves in the faubourg, the roads of which [still] had to run [for

military reasons] in perpendicular direction with regard to the ramparts."

(Maxime LONLAS, "1677 et 1724", p. 2 of 2)

In other words, the houses of the

arsenal workers that moved to the Western faubourg were lined up in East-Westerly

direction along the "chemin de la Rochelle." For strategic reasons, no

houses on roads branching of in a North-South direction were yet allowed.

The artillery of Rochefort needed a largely unobstructed area in front

of the ramparts; buildings that woould provide cover to an enemy in case

of a siege were not welcome.

This is typical for much of the

16th and 17th century, and yet such considerations, in many cases, did

not permanently obstruct the development of faubourgs if economic and social

factors weighed against the military and its obsession with optimal defense.

We are interested in this smal detail

reported by Lonlas because it confirms our hypothesis that workers in Rochefort

were spatially marginalized. Those who moved went from one marginal location

to another.

n 1688

n 1688

Apart from indicating the "ancienne paroisse" and giving us the name of the "chemin de la Rochelle," the 1688 plan is not very conclusive, with regard to the western faubourg. It shows of course the "road network" [Wegenetz] in more detail than the previous plans.

1724

1724

The 1724 plan is trhe first plan that shows a substantial faubourg development, as does of course, to an even greater extent, the subsequent (1845) plan.

1845

1845

We shall not concern ourselves herewith any further with details of the faubourg development which Maxime Lonlas has explored and documented very nicely.

Suffice it to say that the the working

class (or its 17th and 18th century predecessor) which was delegated to

the margins of the grid-patterned town (albeit within the ramparts) and

especially to its wasteland by the river, later on found itself centered

in Rochefort's faubourg(s).

In other words, the concrete line

of separation of the bourgeois and the proletarian

town shifted; but the division was present from the late

17th century beginnings of Rochefort and continues, we may assume, until

today.

Rochefort was after all a modern

town; its foundation fell into a phase of waning feudalist remnants, of

ascending commercial (and agrarian) capitalism, appended by the first beginnings

of an early industrial 'régime de travail.'

Footnote

(1) Maxime

LONLAS, "[Rochefort] Domaine Historique. L'évolution de la ville

d'un point de vue architectural. 1666 et 1672", in: http:/rochefortsurmer.free.fr/hist_archi1.php,

p 2 of 2

Literature

Camille GABET, Le Réseau routier de Rochefort de la fin du XVIIe

au début du XVIIIe siècle.

n.p./ n.d.

Robert FONTAINE, La Paroisse Notre-Dame de Rocghefort au XVIIIe siècle.

Rochefort (Société de géopgraphie) 1993 (104pp.)

Maxime LONLAS, "[Rochefort] Domaine Historique.

L'évolution de la ville d'un point de vue architectural. 1666 et

1672", in: http:/rochefortsurmer.free.fr/hist_archi1.php

*

* *

[Appendix 1]

The "Waste Land, Again

A terrain of inferior quality?

The terrain between grid-patterned town and Corderie

(on the one side) and

the arsenal (on the other) (1)

It is necessary to ask why the grid

pattern of the new town of Rochefort did not extend up to the river.

A lot speaks for the hypothesis

that the terrains close to the river were of inferior quality, either washed

up sands or swamps. It is well-known what constructive difficulties were

encountered when the Corderie - a large and heavy building - was built

on this sandy sub-soil. A large number of workers had to be employed to

make sure that the heavy outside walls as well as the interior walls were

raised simultaneously on all side, in order to keep the pressure even on

the sands below.

This speaks very much against a likelihood that these sites would be in great demand by private builders of heavy stone buildings. They could however support lighter 'cabanes', thatched huts constructed to temporarily house workers. Even larger wooden structure may not have been a problem.

If we maintain (and rightly so, it may be claimed) that the early workers' houses were marginalized and NOT A PART of the comprehensive grid-patterned lay out of the 'ville royale' (which was, in fact, a 'ville bourgeoisie' cut off from the Corderie and the jardin royal), then the terrains left empty between grid pattern and arsenal, a kind of waste land, possibly swampy and unhealthy, is the most likely site.

West

=== > North

=== > North

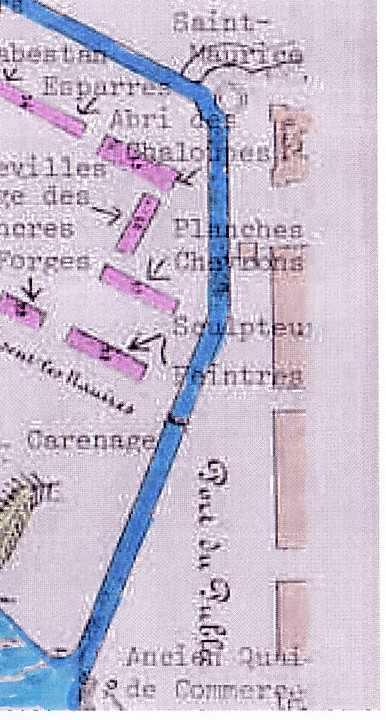

Another exerpt from the post-1672/pre-1677 plan

But other areas, incidentally, were marginalized as well, even though they fell into the grid pattern (or almost so). We are referring here to the area near the Southern ramparts, dominated by the gun powder magazine.

On the pre-1677 plan presented

here (in the form of an extract showing the Southeastern part of the grid-patterned

town), we can identify a 'caserne' near the Southern gate (a bit West of

the powder magazine). This was neither an item that would increase land

values and the desirability to acquire plots here, at least not from a

bourgeois point of view and when seeing the 'caserne' in conjunction with

the powder magazine. (The soldiers in the 'caserne' could be a rowdy lot,

and to have them as neighbors was not the most enviable option.)

But let's come back to the supposed

'wasteland.'

The pre-1677 plan (here another

exerpt) shows us that this part of the town bordered on the ditch or canal

surrounding the 'arsenal' proper (to the South of it), as well as a wide

expanse between it and the 'arsenal' that was left more or less empty.

Are features of the 'terrain' the main reason why neither a grid

pattern nor industrial buildings (of the arsenal proper or the

Corderie complex) were foreseen here for many decades (and possibly are

again more or less absent today)?

Sources speak of marshy areas,

we pointed out. (Nevertheless, the Corderie was built, at great expenses,

near the river embankment. Also, the 'ferronerie', in the 19tth century,

was extended into this waste land.))

Perhaps we can identify two reasons why the area was exempted from the well-laid out town's rational plat.

(1) Space for workers' houses had to be reserved (in the least desirable, least marketable area, yet protected by the ramparts).

(2) If this 'wasteland' led up to the old point of embarkment (the local 'port' that had existed here already before 1666), a continuity of port activity could be envisaged..

In fact, a ships' basin [harbor

basin] was "produced" subsequently at its Northern edge (quite close

to the Corderie); it is already visible on the 1677 plan (a portion of

which is shown below).

1677

1677

The western tip of the basin is barely visible at the right margin

of the plan excerpt

While the plan of 1677 lets us suspect workers' houses between the powder magazine and the château (thus, at some distance from the river), it is the plan of 1688 that allows us to recognize a sensitive new aspect in the zone under scrutiny: a row of buildings close to the arsenal's dutch and close to the riverside.

Yes, at least two large, elongated buildings have been lined up along the Eastern part of the ditch. A combination of other structures, different with respect to the shape of their plat, and forming small 'courts', have been produced adjacent to the former two structures, but not by the ditch; rather, along the Charente.

The makeshift continuation of the grid East of the château allows for an access path leading almost up to the buildings by the river.

If the workers' houses that according to Bourit's source were constructed by the Charente and that according to Lonlas' source were "close to the arsenal" are not in fact these buildings, they must have been very close to them and would have been omitted, in that case, from all available plans known to us.

As noted already, the possibility that warehouses were produced near the 'ancienne quai de commerce' cannot be totally ruled out.

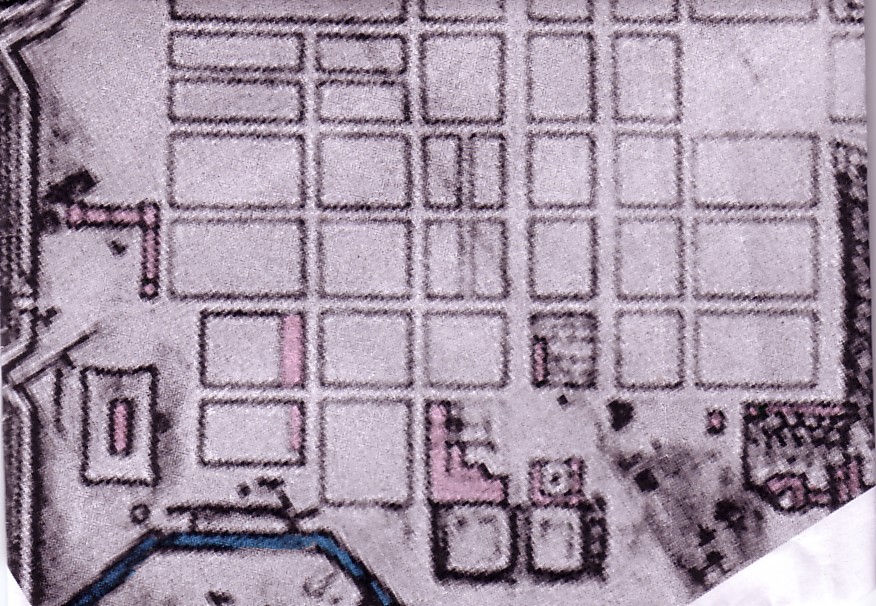

This plan is all but accurately drawn. The blocks extending from

the gun powder magazine to the château appear to be drawn to large,

in relation to the canal (or ditch) and in relation to the terrain surrounded

by these blocs, the canal, the Charente, and the Corderie site.

The plan is valuable because it shows a building near the junction

of Canal and Charente.

At any rate, with the deplacement

of arsenal workers living here in this area and the later (likely) resettlement

of the 'officiers du roi' who bought their 'maisons,' the way became free

for industrial and possibly also additional harbor development. We have

already noted the expansion of the arsenal forges (the "ferronerie" of

the 19th century), as presented by the 1845 plan.

* * *

Appendix 2:

The Arsenal

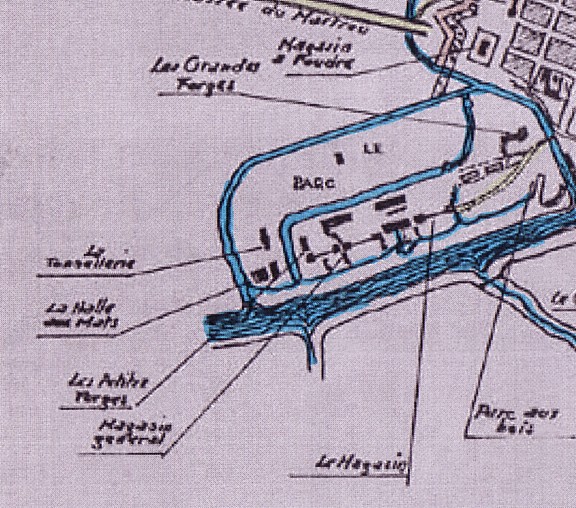

The arsenal (when almost completed in 1677) and Rochefort

1688

1688

The only access to the arsenal in 1688 is via the bridge to the

East of it..

pre-1677

pre-1677

The arsenal and the portions of Rochefort closest to it

The workers of the arsenal could hardly accept long journeys to work

if inhabitable, even 'valueless' terrain lay in front of the gate

(or access bridge [pont public] of this Navy yard. In all lilelihood we

have to assume an organic relation between the site of the ateliers and

the three buildings just a bit North, close to the river.

(This would confirm the information supplied by Antoine

Bourit who points out that "Colbert de Terron fit construire des bâtiments

collectifs, provisoires le long du fleuve pour y "camper" la population

[ouvrière]".)

It also coincides with Maxime Lonlas' information that the arsenal workers

(or a certain number of them) possessed "maisons" (houses) "à proximité

de l'Arsenal" [close to the arsenal]. Especially if we keep in mind that

the blocks of the grid patterned town closest to the arsenal (near the

gun powder magazine) where not even partly filled with buildings, by 1672.

17th century

17th century

The Arsenal and the nearest blocks of the town. This plan is all

but accurately drawn.

Footnote

(1) It is necessary to remind the reader

that the plans and plan excerpts shown in the diverse PARTS of the CHAPTER

ON ROCHEFORT are based on plans published by Maxime LONLAS

and also (in a few cases) by Antoine BOURIT.

These two authors have drawn on archive material

that has not been accessible to us since , at the present stage, our limited

research funds have restricted the possibilities to travel and visit the

archives we woould like to consult. In so far, this study can truly be

considered as no more than the "Prolegomena" to a more extensive and better

founded (and financed) study.

Literature on the Arsenal

[Literature on the Corderie has not been listed here]

Martine ACERRA, Rochefort et la construction navale française:

1661-1815.

Paris (Librairie de l'Inde) 1993 (4 vols.)

Maurice DUPONT / MARC FARDET (preface by Etienne TAILLEMITE), L'Arsenal

de Colbert. Rochefort.

Rochefort 1986

de BON et al, Les Ports militaires de la France: notices historiques

et descriptives.

Paris 1974 [reprint of the 1867 edition]

René MÉMAIN, Le matériel de la marine sous Louis

XIV [...].

Paris (Hachette) 1936

Jean PETER, Le port et l'arsenal de Rochefort sous Louis XIV.

Paris (Economica) 2002

Jacques PINARD, Les Bâtiments industriels de l'ancien Arsenal

de Rochefort.

La Rochelle 1979